|

Venice as maze

We say easily that some place feels “maze-like“, but

Venice really does. Like those other towns, it's not topologically

a maze, in the sense of having ways that spiral in on themselves

or wrap around each other or lead a long way to nowhere, but it

feels like a maze in that you just cannot find your way across it

by taking direct routes. There are no direct routes.

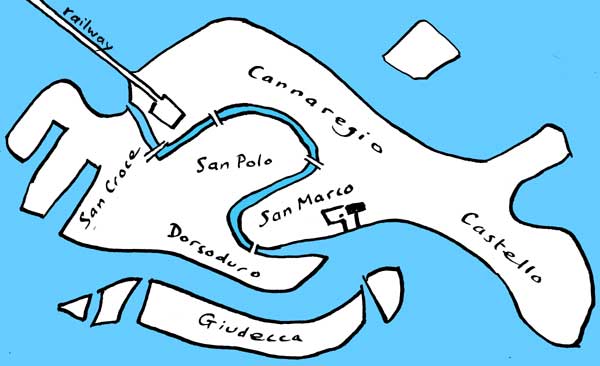

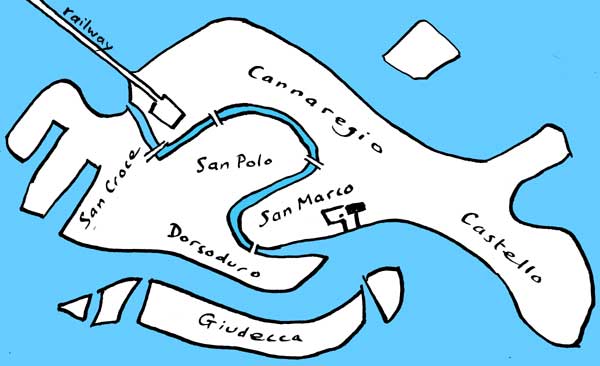

There is just one large simple form,

the Z (really a smooth backward S) of the Grand Canal. It serves

to divide the island city into describable pieces: San Polo and

San Marco within the two curves, Cannaregio and Castello and Dorsoduro

and San Croce around (though these pieces do not at all closely

correspond to the mazy boundaries of the six traditional sestieri

with the same names). To link the regions, there are only the three

bridges — Scalzi, Rialto, Accademia — across the Z of the

Grand Canal. (This was before the recent building of a western steel

bridge at the Piazzale Roma.) To get expeditiously between points

far apart, the only way is to go by vaporetto, water bus,

along the Grand Canal. On land there are very few ways that continue

more or less unbroken for distances more than a hundred yards: the

Strada Nuova in Cannaregio, and some fondamente along canal

sides. Even these are interrupted, like every other way, by the

stepped humps of the bridges over the small canals.

(There are no wheeled vehicles in Venice,

except handcarts, and tourists' wheeled luggage. Not quite true

since Mussolini built the long bridge that carries the railway and

also a road into the industrial northwest corner of the city. Even

bicycles aren't supposed to be allowed, though one shows furtively

in a painting I did on my first visit to Venice.)

Every other street or passageway is

in short bits, which rapidly debouch into cross-bits, unless they

turn corners, open into campi, or dead-end into walls or

into canals. (I have come very close to stepping off a passageway's

end into a canal.) The buildings are rectangular or nearly so, and

line up along the Grand Canal or some of the sides of campi,

but they have been shaken together in a centuries-long sieve. The

mass of buildings and slits between them gradually shifts orientations,

so that it's no use trying to keep your continual left and right

turns to a general direction; your general direction curves, and

sometimes comes around in a circle. If you ask directions to somewhere

you get a pointed finger and “sempre diritto” —

but there is no diritto in Venice!

The only way, if you don't know the

way, is to discern a crowd and follow it. Here and there, even late

at night, you come across a thickening of people, very much like

ants who know they are on a trail because they keep bumping into

their fellows. They are going one way toward San Marco and the other

way toward the station (the Rialto being the mid point between them

through which most journeys have to go). So you guess left or right

and follow them; and because of the ant-trail you know not to stay

with, for instance, the relatively wide and straight Calle dei Botteri

but to turn into one of the slits in its side.

Someone born in Venice and going to

another city may find its blocks or wedges of streets crassly simple.

A Venetian could surely not get lost in any other city! We might

find that Venetians are winners at maze-solving.

Helpfully to tourists the municipality

has put up many arrowed signs along the ant-trails:

<— SAN MARCO RIALTO— > STAZIONE—

>

On one wall near the Santi Apostoli, signs point toward the very

remote STAZIONEin opposite directions!

And the canals — that is, the

small ones, called rii. Before going to Venice I imagined

it to be a number of islands, with a sort of village sitting on

each and looking out across its surrounding bridges. Well, there

may once have been on each island its village, which grew outward

to fit against the surrounding water and narrow it to a canal; but

it doesn't appear like that, except that there are the campi

or “squares“, many of which still feel like the hubs of

villages. You are aware mostly of the mass of stone, finding your

way around inside it — turning corners, passing between pillars

and under arches and around the rambling limbs of churches —

and at unexpected moments you come across a piece of a canal, like

a bit of broken glass glittering among bricks.

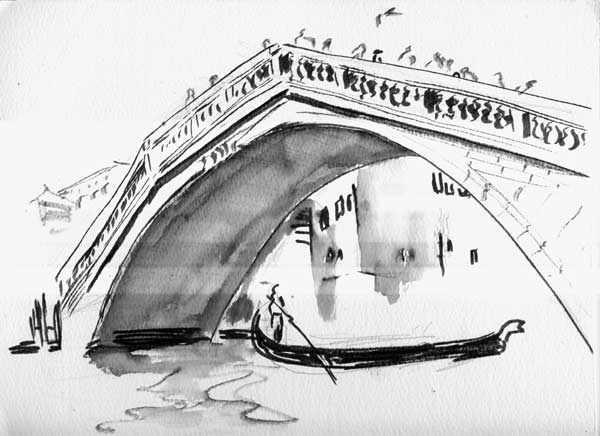

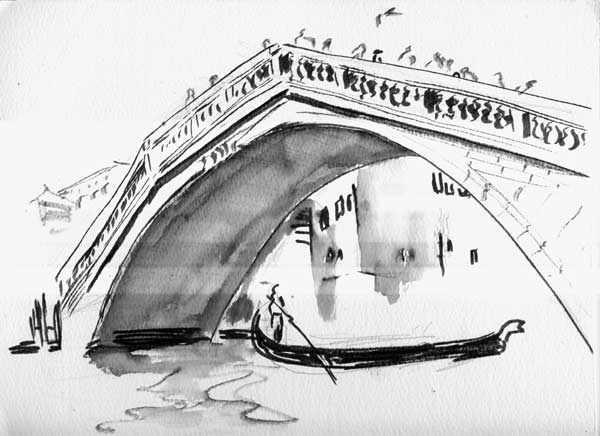

The bridges — all high semicircular

humps of white stone to let standing gondoliers pass under, with

seven to ten steps up each side — are themselves, some of them,

like little villages with room to congregate: because the openings

they connect may not be opposite to each other, and may be more

than one to each side. I think the most spacious, and almost impossible

to draw the plan of while standing on it, is the one that evolved

to get from San Giovanni Crisostomo to the Campo Flaminio Corner

north of it.

There is a fine large map that you

can buy; it appears to show, in pleasant color, the shape of every

block of buildings, every alley and courtyard. This map, though

it has only a few mistakes (Campo Santa Maria Nova has an extension

because a building is missing), compounds the maze. The map may

give street-names that it considers correct though people no longer

use them, the street signs may give dialectal forms — or vice

versa. We were directed to the street called La Merceria; but that

name applies on the map to one street, in reality to a group of

several little streets roughly alongside each other like tines of

a fork; the signs posted on them say (for instance) Marzaria del

San Salvador o de Capitello; the map gives them yet other names.

You come to a sign that says: Ponte Giovanni Andrea de la Croce

o de la Malvasia. Can you remember that? — and how do you parse

it, is “de la Malvasia” the alternative name of Giovanni

or of the bridge?

On the map it may appear that the

route you want to take — even one of the main ant-trail routes

— does not get through at all; or that there is no way to get

to one of the landing-places of vaporetto or traghetto

on the Grand Canal's sides. If you look at the map more closely,

there are little dashed lines: there is a way under the buildings,

a sottoportego.

I recognized the view I had so elaborately

drawn during my first visit to Venice long ago: we were on the Ponte

de Bareteri, looking along a short stretch of canal to where it

runs into another at a T. Tilly saw among the windows in the farther

wall of the crossing canal a “Camere” sign; wouldn't it

be good to lodge at this spot, in my painting? and she set off to

inquire at the place, which seemed not far away. As soon as I, left

on the bridge, looked at the map, I knew I shouldn't have let her

go. It wasn't totally impossible to get to the other side of that

building from here, but it involved a detour of seven times the

distance, false turnings to avoid, another bridge, garden gates

— I knew she'd be lost. She was, and I could only wait for her

to find her way back.

The campo that feels most like

a village, somewhere in the San Polo region, is San Giacomo dell'Orio

(one of the less easy names to recall in a hurry!). It's an ample

space because it wraps around its church, which is externally a

rambling dusty heap of round apses and has the usual art to boast

of inside. There are trees, benches, a shop, café tables; dogs,

birds, and people hang out; drifts of children cross on their way

from school, and play with balls and skateboards. One of the openings

piercing the smoother of the two long sides happens to be that leading

to Venice — to mainer parts; the others prove to be tunnels

ending in wharves on a canal. On the other long side, one of the

ways around the church leads (past the opening of a hidden courtyard)

to a sub-campo beside another canal, with more tables and a bridge;

two others lead to two other bridges, which can see but not communicate

with each other. The tapering end of the campo (Calle Larga,

though not at all wide) becomes a sort of grotto easier to draw

than concisely describe: yet another canal, turning a corner, the

usual humped bridge with chain of figures loitering or hurrying

over it, restaurant tables crowding points on either side, alley-streets

slipping away slit-like to three destinations.

There are, in the cores of other old

cities, similarly dense webs of alleys and piazzas and perhaps even

canal-glimpses, but the web of Venice is vast. It's all core. Just

glancing at the map, or opening a guide-book and seeing all the

chapters on the component districts, you are impressed by its vastness.

It extends over almost the whole main island, that is, the island-mass,

as much as — well, on measuring it I find it's only about a

mile and a half wide. It seems several times wider, presumably because

walking across it is such an intricate labor. That's why, though

Venice is now injected with ridiculously large hordes of tourists,

they don't seem dominant except in their concentrations around the

station, Rialto, and San Marco. The mass absorbs them, like particles

in the passages of a lung.

Venice is — to under-state —

pleasant to arrive at. You cross the lagoon in the train, come out

of the broad front of the station; broad steps descend to the bank

of the Grand Canal, at left is the Ponte dei Scalzi (“of the

barefoots”); you ascend it and descend into the maze. I conceived

of making a Venice Maze Game: you find yourself in a little street

that leads straight ahead, in the general direction of Venice's

heart, you quickly come to a point where there is a turning you

could take to the left, but you ignore it and go ahead — and

the little street dead-ends. You have to go back and take that other

turning, over a canal, and so it goes on.

Ponte Scalzi

Back

|