|

Atrani between headlands

The southern coast of the Sorrentine peninsula is a steep landscape

of spurs from the Lattari mountains descending into the Mediterranean.

The road scrapes high along these hillsides. I was cycling up the

leg of Italy from south to north, and should have kept to the right,

but I rode on the left so as to see down the cliffs, and the Italian

drivers, coming at me so suddenly around the bends, didn't have

time to emit their usual sociable horn-blasts. I looked down to

little places such as Erchie beside the sparkling sea.

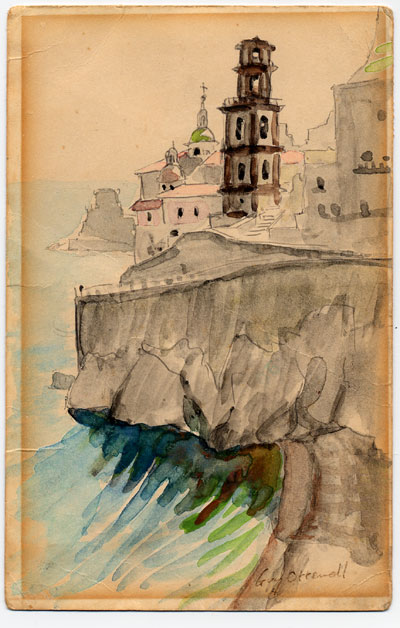

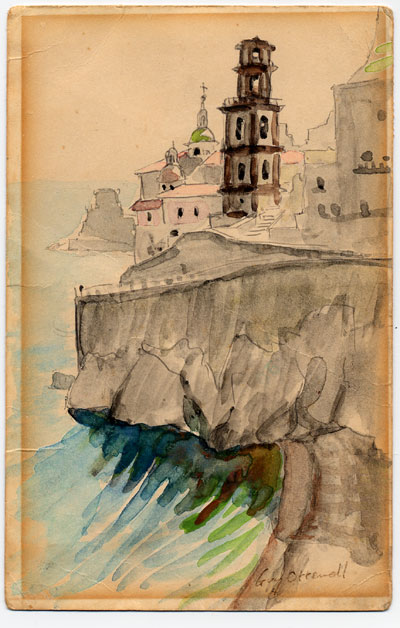

Ahead I saw a church on a corner. (The sketch I made has become

brown because sent to someone as a postcard and left in sunlight.)

And on rounding that headland I saw Atrani in its valley. It seemed

late afternoon, because the town was already submerged by shadows

that dropped like spears from the higher ridge on the farther side.

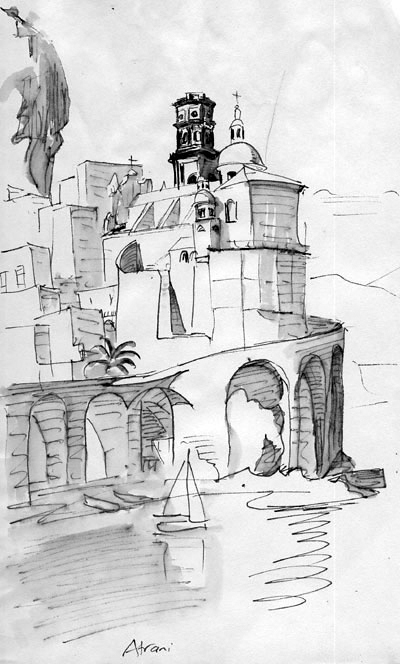

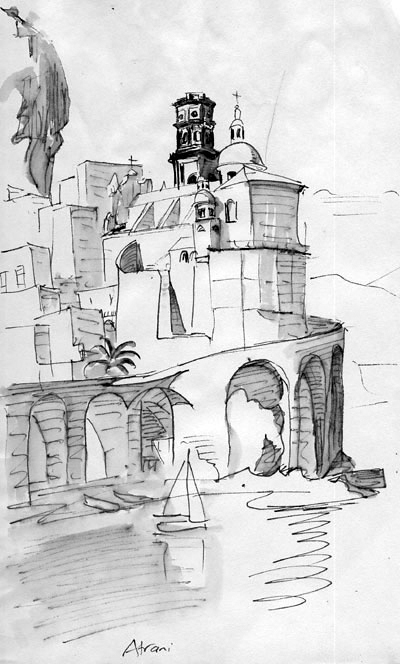

The coastal road swooped across the front of the valley on high

arches, and there seemed at first no way down into the town!

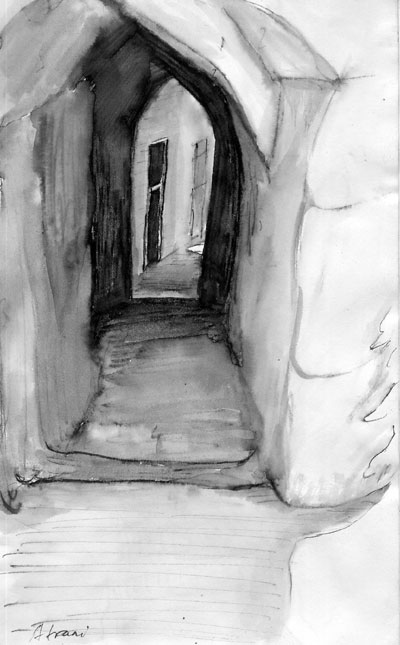

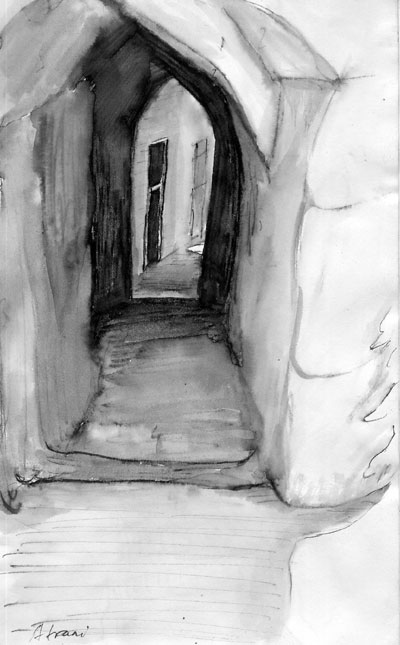

There was of course a way in: the top of this viaduct was wide enough

to be a small park; from the balustrade at the back of it I could

see straight down to the towns's middle, the piazza; and there was

a sort of puncture in the viaduct, through which steps descended

in several twists, three storeys, passing the thresdholds of dwellings

inside the structure, to emerge in the piazza, which as in any Italian

town is the theatre of life.

Around the piazza

the houses cram, piled on each other, a dense mass threaded by passages

and arches and many flights of steps — but no streets! No streets

except one, which does not look very street-like: it comes down

(under an arch on which stands another church) into a corner of

the piazza, and is paved with cobbles in that fashion that looks

like curving wave-fronts. (It is a slightly mystifying pattern because

where the waves overlap you can't distinguish which wave some of

the cobbles belong to.) Thus the street suggests a shallow river

rippling downhill. And indeed it is built over and hides the stream

that runs down the valley.

This first time

that I discovered Atrani, I stayed in a room that was rather cold

because so deep in the pile of whitewashed passageways.

The passageways led up to a path etched into the eastern cliffside,

whose volcanic-looking rocks were sometimes overhead.

The path climbed past a third church (Santa Maria del Carmine) on

a ledge. The floor of the valley, climbing alongside, was terraced

with vineyards. Up ahead on the horizon I could see houses I thought

were in Ravello, to which I had been told the path led.

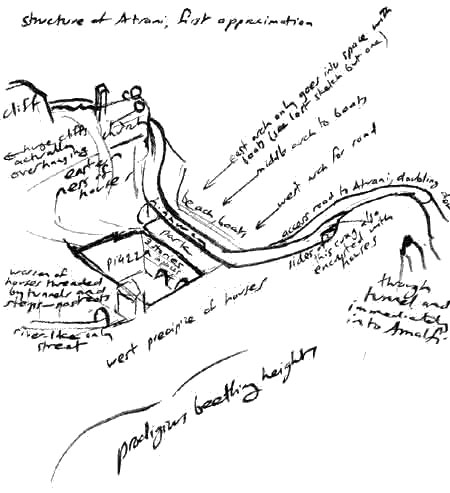

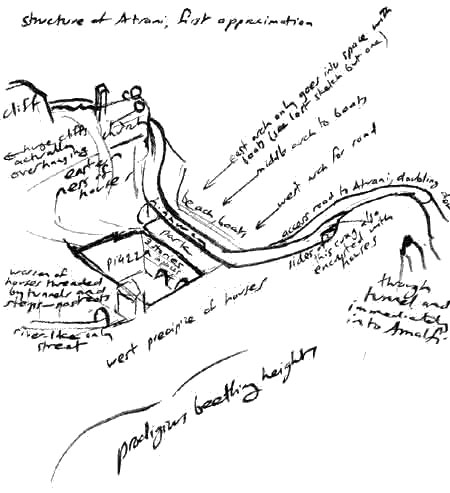

If you go on along

the viaduct, how does the highway get out past the other wall of

the valley, the western ridge? Through a tunnel! The tunnel emerges

in another town (larger and more famous), Amalfi!

The structure of Atrani was so interesting that I made myself a

diagram of it before riding on along the coast.

But later visits to a place modify the conception of it.

That tunnel, for

instance: the impression was that it bores through the high rocky

ridge separating Atrani from Amalfi. But really it is cut not far

into the toe of the ridge; it must have been undertaken as a rather

slight straightening of the highway. The older narrow road went

around the end of the cliff; the ledge is still there, might have

been left as a footpath so that pedestrians don't have to walk through

the booming tunnel along with the cars, but was allowed to become

an open-sided restaurant.

And the tunnel does

not emerge directly into Amalfi: the ridge's descending end is forked,

so that there are a couple of curves before you come in sight of

Amalfi and glide down along its marine esplanade.

Looking up at the

wall supporting the highway as it wraps around the crag topped by

the church, you can see that it is not all of a piece: the lowest

part is quite ancient, and there are two changes of masonry above.

There must have been a time when there was no road around the cliff.

The mouth of every valley that descends to this coast has come to

be packed with a village or town, and most of these places will

once have been connected only by mountain paths and by boat (as

is still the state of the Cinque Terre or “five lands,”

villages on the Ligurian coast). But a coastal road was made, mostly

quite high along the mountainsides; to reach Atrani it descends,

and a ledge was cut around the foot of each of the cliffs. The eastern

one was raised by stages, and about 1950 came the viaduct across

the front of the town and the tunnel through the other headland.

I wonder whether this was felt, at the time, rather like an imprisonment

behind a sort of freeway overpass.

Of the viaduct's

arches, the western one goes through to the river-street, though

in a crooked way leaving corners for restaurants; the middle arch

goes through to the middle of the piazza; the eastern opening becomes

an inlet where fishing boats are beached.

It's not quite true

that the road system of the outside world does not communicate with

Atrani. From just before the tunnel, a roadway peels off and curls

back down to the beach and thus gets in through the middle arch.

There is a car park by the sea, and an occasional car comes in to

take a guest to a hotel up at the end of the single street and of

the town. That's how it was when we were there. Atrani seemed essentially

car-proof, so that tourists stayed elsewhere. I suspect there are

now more cars and hotels.

The river-hiding

street, the second time I saw it, had been re-paved — “Yes,

several times. The cars wear it out.” The wave pattern was

still used, but instead of stone cobbles there were small pink tiles,

with white ones tidily marking the curves — which faced uphill!

So the suggestion of the subterranean water had been in my imagination.

East of the piazza,

several threads of alley and stair lead surprisingly up to the conspicuous

church on the promontory, the Maddalena, which stands on top of

several levels of houses. On the western side, an even more surpriseful

tangle of routes climbs through a honeycomb of dwellings and gives

birth to a path along the hillside to Amalfi.

The older church

down in the center, straddling the street as it debouches into the

piazza, was shut up, awaiting repairs. Thirty wide steps leading

up from the piazza to the church are the young men's usual evening

hang-out. The church's name is San Salvatore de' Bireto. Why of

the beret or cap? Because this was the headgear of the doges of

Amalfi. They were crowned with it in the church of Atrani, which

was Amalfi's smaller sister and possession.

In the Middle Ages,

when Italy was always fragmented between many states, there were

ports around its coast that were “maritime republics,”

city-states that knew how to deal with the Muslim lands across the

Mediterranean. The four major ones were Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and

Venice. They are always listed in that order, which is the order

of their seniority, or at least of their peaks of power, and roughly

the inverse order of their size. Their flags, arranged in the same

order clockwise from Amalfi at top right, make up Italy's naval

flag. In the same order they host each June the regatta of the Maritime

Republics. Small Amalfi's turn came around in 2012, so we were there

for the pageantry.

An encomium in Campanian dialect by Michele Buonocore:

Quanno ce fu ’o Big Beng

se rrevoltaje ’o creato.

Da cielo se ne scennette

’no piezzo ’e Paraviso

che miezz' ’a doje montagne

restaje ’ncastato:

era nato Atrane e da tanno

sta ancora l’a appiso.

Translated for me into standard Italian by our host at a restaurant:

Quando ci fu il Big Bang

si mise sotto sopra il creato

dal cielo scese un pezzo di paradiso

che reste incastrato tra due montagne:

era nata Atrani e da allora sta li ancor appeso.

—“When the Big Bang happened, creation began upside down.

From the sky fell a piece of paradise, which stopped and stuck between

two mountains. Atrani was born, and has been hanging there ever since.“

|