|

Bivalve Dubrovnik

A Yugoslav ship taking me from Greece to Trieste touched at Dubrovnik,

but I must have seen little beyond the harbor. I was more impressed,

farther along that Dalmatian coast, by Split, a city built inside

a building: that is, the old part of the city, a dozen or so blocks,

is inside the square walls of a single huge building, the palace

of the Roman emperor Diocletian. The very name, Split in

Croatian, Spalato in Italian, comes down from Latin palatium,

“palace.” Or so I thought and so was the belief, but scholars

now tell us it derives from an earlier settlement called Aspalathos,

which was the Greek word for the spiny broom. This shrub coats the

hillsides of the Dinaric range with the yellow of its small flowers,

and that was what first impressed me when I came back years later

to Dubrovnik, looking down from a plane.

The second impression

was the intense delight of putting my bicycle together in the small

airport and riding out past what I at first took for a garden. It

was a polje, one of the blocky depressions in the karst limestone

landscape, floored with turf and poppies. I would have liked the

fourteen-mile ride along the sunny upland to go on for ever. When

I paused to sketch the first view down to Dubrovnik nestling by

the sea, a military policeman on a motorcycle paused to determine

whether I was a spy. I came down, down to the walled city and entered

it through a twisty side-gate in one of the gates,

and spent a week rambling among the details of the masonry.

You can walk around

Dubrovnik along the top of its protective wall,

which enchains various towers and castles. Projections on the southern

side look down crags to the sea, and on the northern side into what

used to be a moat. And on the inner side you can sometimes look

down into courtyards and see people hanging out their washing or

playing cards. Steps descending from the wall involve it in the

upper ends of little streets,

all of which slope away down from it. The two networks of streets,

southern and northern, meet in the one level and wide street, called

the Placa or the Stradun (formerly in Italian the Stradone).

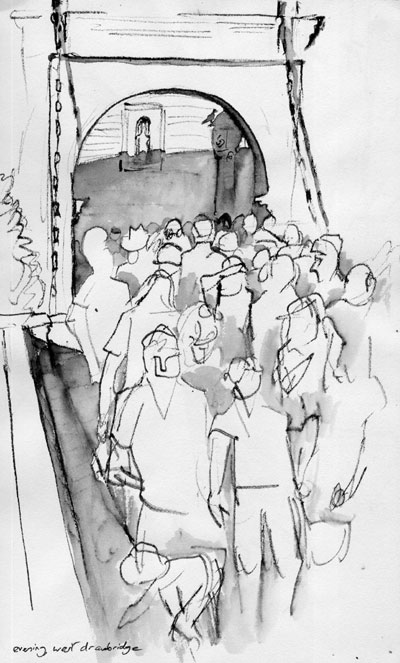

The Stradun is like

a river of white stone polished smooth by feet. For in the evening

it is filled with a river of strolling people: here as in other

Mediterranean lands life is made happy by the promenade, called

in Dalmatia the korzo. Over the heads of this river of people,

half way up to the eaves of the Renaissance palaces on either side,

skims a layer of birds — swifts and swallows in their thousands,

consuming an invisible layer of midges.

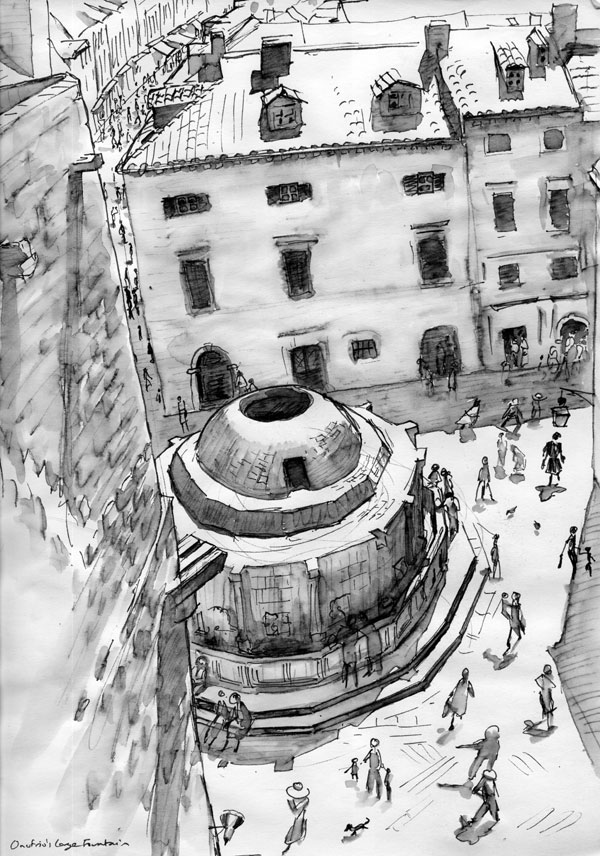

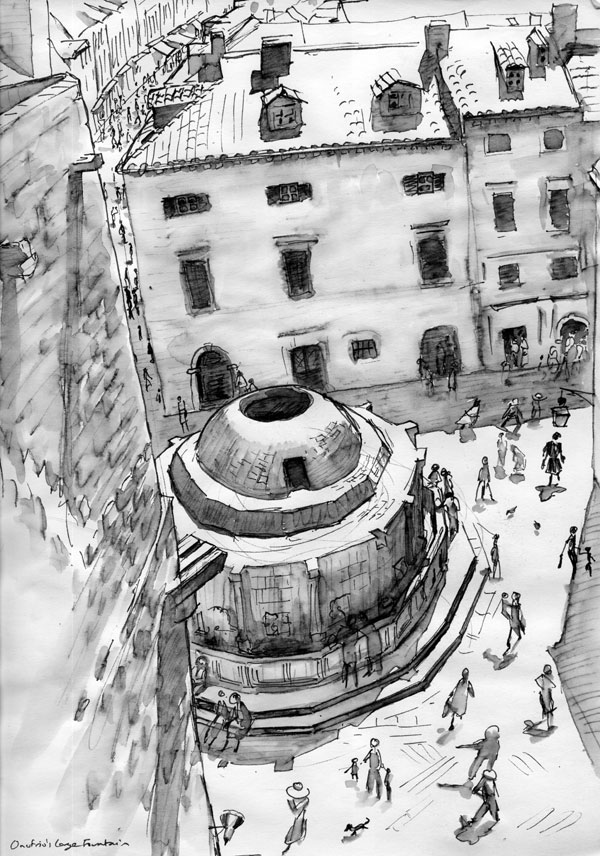

At one end the Stradun

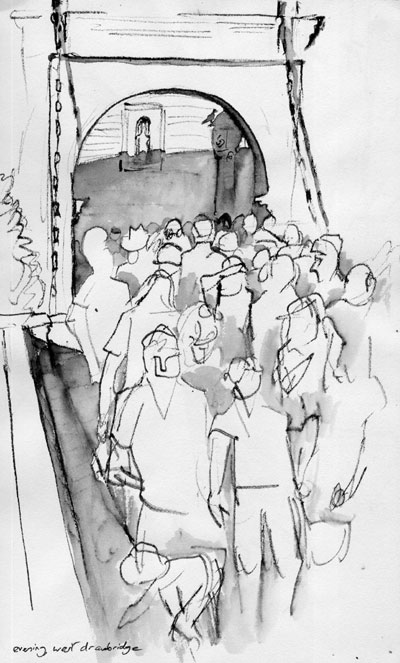

opens past a tower to the harbor. At the other, the strolling people

flow through a square containing a round fountain-house

and out through a gate

and over a bridge across the moat, into the older part of the newer

town. Like other old walled towns, Dubrovnik's is dwarfed by more

recent sprawl, especially onto a peninsula to the northwest. (Split's

sprawl is far larger.)

The wall-girt city

is like a clam, a bivalve shell that has been laid open. Or it's

like a theatre, with two audiences looking down on the Stradun,

the stage where social life happens. It looks like two communities

facing each other with a river between them, and that is what it

once was. The images of “river of stone” and “river

of people” came into my head before I knew that the Stradun

once was indeed a river, or at least a channel.

On one side was

the island city Ragusa, on the other the shore community Dubrovnik.

The wider region (called in ancient times Illyria, in the twentieth

century Yugoslavia) was once part of the Roman empire, and as this

retreated it left a population of Latin-speakers; they were overrun

by Slavs and Hungarians, but communities speaking Romance (that

is, Latin-descended) languages survived: the Romanians, the scattered

groups called Vlachs, and the Dalmatians along the Adriatic coast.

Some of these Dalmatians, in the seventh century, took refuge on

the island from the Slavs. (Archaeologists now think their settlement

was not the first: there may have been a Byzantine and a still earlier

Greek one.) Just across the narrow channel, Slavs came to live,

and they called the place Dubrovnik because it was “wooded.”

The two communities merged, and probably “Ragusa” was

what you called it if you were speaking Ragusan, “Dubrovnik”

if you were speaking Croatian. (There is a more ancient city called

Ragusa on a hilltop in Sicily. The name, I think, has a sexy

ring for Italians because of its similarity to ragazza, “girl.”)

The Ragusans for a long time tended to be the aristocracy, but one

of the many admirable aspects of the flourishing state developed

by the joint community was its honoring of liberty: it was a pioneer

in abolishing slavery, and the motto “Libertas” on the

pennants of its trading ships earned them welcome around the world.

It was early with almshouses and hospitals, was a refuge for Jews.

Ragusa was a Maritime Republic that rivalled the Italian ones of

Venice, Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi (and had a cross-Adriatic alliance

with Ancona so as to get around Venice for trade with northern Europe).

It was a power out of proportion to its size; its policy was to

rely on trade rather than territory, of which it had only a narrow

strip along the Dalmatian coast. At other times it had to compromise

with larger powers, and came under the rule, at least nominally,

of Byzantium, Venice, Hungary or the Turks. Trade declined, as for

Venice, after the opening of new routes to the East; the Ragusan

language gradually died out; an earthquake smashed the city in 1667,

so that only a few of the beautiful palazzi date from before

then. Napoleon put an end to the Ragusan republic, as he had done

to the Venetian, and on that day the Ragusans painted all their

flags and coats-of-arms black in mourning.

After I was there,

Yugoslavia (“southern-Slav land”) broke up and war broke

out among its peoples. Close above Dubrovnik looms 1400-foot Mount

Srdj like an enormous loaf. From it, starting in October 1991, Serbian

artillery bombarded the gem-like town for seven months.

|