|

Istanbul and the City of the Blind

You may have opened an atlas and noticed a remarkable piece of

geography: something that looks like a river, snaking through a

block of land between two seas. The river is in two parts, called

the Bosporus and the Dardanelles (or Hellespont), with a miniature

sea called Marmara connecting them.

This triple waterway

marks for us the juncture between Europe and Asia. And it is indeed

a kind of river, flowing westward, from the Black Sea into the Aegean.

That is, the top level of the water flows that way; there is a smaller

under-current back the other way. During the last ice age, when

the seas were lower, there was no water connection through here

and the Black Sea was a lake in a depression, like the Caspian.

When sea level rose, the “river” made its way through,

and some archaeologists think it first broke through the Bosporus

as a tremendous cascade, accounting for the legend of the Flood.

This triple waterway

marks for us the juncture between Europe and Asia. And it is indeed

a kind of river, flowing westward, from the Black Sea into the Aegean.

That is, the top level of the water flows that way; there is a smaller

under-current back the other way. During the last ice age, when

the seas were lower, there was no water connection through here

and the Black Sea was a lake in a depression, like the Caspian.

When sea level rose, the “river” made its way through,

and some archaeologists think it first broke through the Bosporus

as a tremendous cascade, accounting for the legend of the Flood.

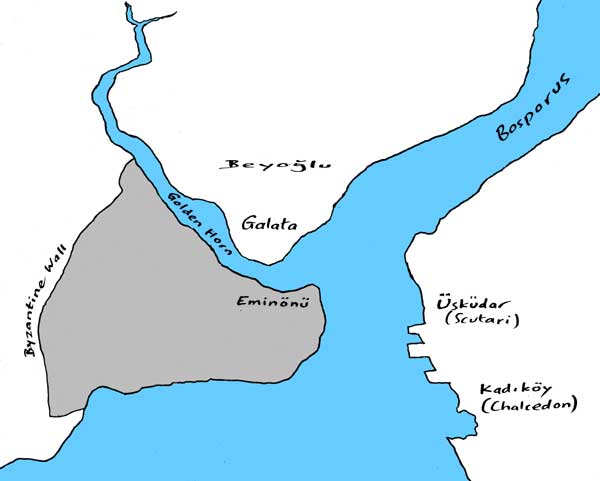

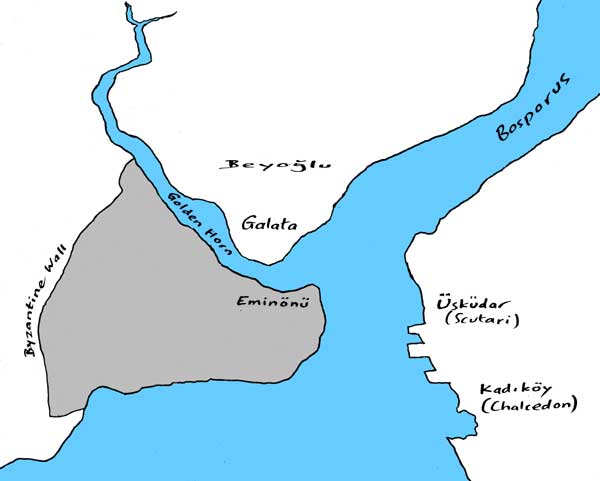

Along these straits

go commerce from one sea to the other, and across them commerce

and migrations from one continent to the other, so it is no wonder

that forts and towns were founded along their banks to control them.

Troy was one of the most ancient, at the mouth of the Dardanelles.

The Bosporus offers even better control, being less than two miles

wide (less than half a mile in some parts). In 685 BC, colonists

from Megara in Greece founded Chalcedon, on the eastern corner of

the mouth where the Bosporus enters the Sea of Marmara. Yet they

could easily have seen that the opposite corner would have been

a better choice, because it had a fine sheltered harbor, opening

right next to it into the Bosporus: a three-mile-long estuary, which

we call the Golden Horn.

The Megarians could

have lost that chance to some other of the ambitious Greek cities,

but they were lucky: seventeen years later, when they were ready

to send out another colony, the Delphic oracle told them, using

the cryptic language of oracles, to build “opposite to the

blind.” “The blind”! — they saw what it meant:

Chalcedon. So they settled, under their King Byzas, on the western

corner, which became Byzantium. Chalcedon soon came under the rule

of Byzantium, and was mocked long afterwards as “the city of

the blind.”

“Constantinople

is a very long name; how do you spell it?” runs the schoolboy

joke, the answer being “I T.” The name may not be the

longest of all placenames (that distinction is claimed for Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogococh

on the Welsh island of Anglesey or Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu

in New Zealand), but the city may be the one that has had the most

names. To tell its names is to tell its history.

“Constantinople

is a very long name; how do you spell it?” runs the schoolboy

joke, the answer being “I T.” The name may not be the

longest of all placenames (that distinction is claimed for Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogococh

on the Welsh island of Anglesey or Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu

in New Zealand), but the city may be the one that has had the most

names. To tell its names is to tell its history.

Before Byzantium,

there had been Lygos, a settlement of the indigenous Thracian tribes.

In 330 AD Constantine, the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity,

chose Byzantium as the new capital of the empire, calling it Nova

Roma (Latin) or Nea Rhoma (Greek), “new Rome.” (Constantine

did not impose Christianity, but imposed toleration of it. And he

did not divide the empire into its western and eastern halves; that

had been done by Diocletian just before him, and he reunited it;

the division happened again in 395 and became permanent.) Later

the city became known as KŰnstantinoupolis, “Constantine's

city.” After the collapse of Rome itself in 476, the eastern

empire became the only Roman empire. Though calling itself that,

or just Romania, it was Greek in language and culture; and people

often called the great capital just hÍ polis, “the city,”

and talked of going “into the city,” eis tÍn polin.

For a thousand years the Byzantine empire lasted, undergoing times

of expansion (from Spain to Armenia) and times when it shriveled;

lost its heartland in Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks in 1071; the

city was looted by other Christians — Crusaders from the west

— and had to be abandoned for sixty years; the empire recovered,

but feebly; became surrounded by the Ottoman Turks, to whom at last

it fell in 1453. From eis tÍn polin came the Turkish form

Istanbul. The modern Turkish alphabet writes this with a dot over

the I, because there are two i vowels in Turkish and this

is the bright front one. Europeans turned KŰnstantinoupolis into

Constantinople and Istanbul into Stamboul.

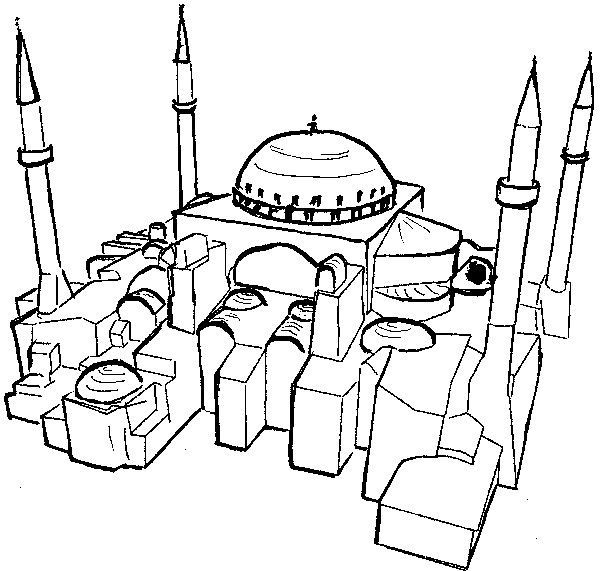

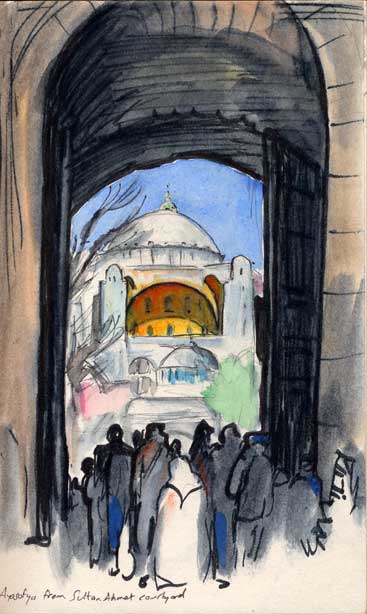

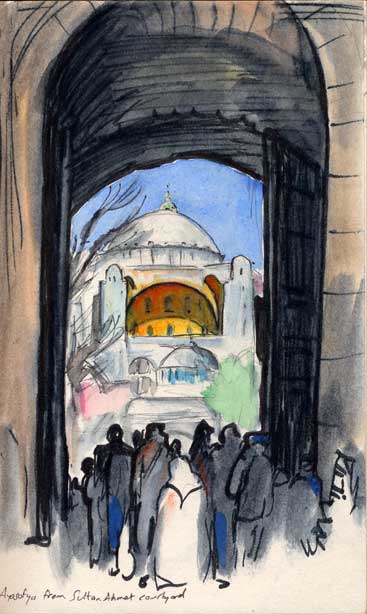

Constantinople's

great church has also been a name- and function-changer: Hagia Sophia

(“holy wisdom”), in Latin Sancta Sophia or Sancta Sapientia,

in Italian Santa Sofia, in Turkish Ayasofya. The “wisdom”

to which it was dedicated was the Logos, the Word, which according

to the Gospel of John became incarnated in Christ. It was built

around 530 under Justinian at the height of Byzantine power, and

it was the largest of all cathedrals till surpassed by Seville in

1520. In form it is a hemispherical dome supported by four semicircular

arches, two of which are the fronts of half-domes, below which are

smaller half-domes, and there are vaulted spaces around — a

cluster of domes, making a symmetrical mountain of stone.

The Turks

converted it to a mosque and set at its corners four minarets, like

tall pencils. In the 1930s it passed from mosque into museum.

It was the inspiration

for the masterpieces of Turkish architecture: many mosques resembling

it were built in the late 1500s by Sinan (who was a Muslim of Greek

origin) in Istanbul and also at Edirne, deeper into Europe; and

around 1600 Sultan Ahmed's mosque, called the Blue Mosque, arose

on the former site of the Byzantine palace, facing across a garden

to Hagia Sophia.

The first time I passed through Istanbul and crossed by ferry from

Europe to Asia, I looked around and thought of the scene as a magnified

village pond, around which stood the multitude of minarets.

The promontory between

sea and harbor remains the city's nucleus. It is called Saray Burnu,

the headland of the seraglio, and on it, surrounded by gardens,

is the TopkapI, the “gun gate” palace; a little farther

back, the great mosques. The city of Byzantine times spread about

four miles back to where its wall, four miles long, curved from

Golden Horn to Marmara — the enormous wall that failed to keep

out the Crusaders and the Turks. And in later ages the city spread

and spread, becoming a cluster of cities on both sides of the Golden

Horn and on both sides of the Bosporus. It embraces Chalcedon (now

KadikŲy) and Scutari (‹skŁdar) and other places in Asia across the

Bosporus, and Galata across the Golden Horn and other satellites

on the European side. It is not so much a city as a built region,

stretching twenty miles or so into Europe, almost as far up the

Bosporus, and twice as far along the Asian shore. This region is

shaped the way it is by a web of geological faults. And much of

the hasty growth is in box-like frames of concrete filled in with

skins of brick, which collapsed in the earthqueke of 1999 (the day

after I left), killing 17,000. Yet the slender minarets stood.

|

This triple waterway

marks for us the juncture between Europe and Asia. And it is indeed

a kind of river, flowing westward, from the Black Sea into the Aegean.

That is, the top level of the water flows that way; there is a smaller

under-current back the other way. During the last ice age, when

the seas were lower, there was no water connection through here

and the Black Sea was a lake in a depression, like the Caspian.

When sea level rose, the “river” made its way through,

and some archaeologists think it first broke through the Bosporus

as a tremendous cascade, accounting for the legend of the Flood.

This triple waterway

marks for us the juncture between Europe and Asia. And it is indeed

a kind of river, flowing westward, from the Black Sea into the Aegean.

That is, the top level of the water flows that way; there is a smaller

under-current back the other way. During the last ice age, when

the seas were lower, there was no water connection through here

and the Black Sea was a lake in a depression, like the Caspian.

When sea level rose, the “river” made its way through,

and some archaeologists think it first broke through the Bosporus

as a tremendous cascade, accounting for the legend of the Flood. “Constantinople

is a very long name; how do you spell it?” runs the schoolboy

joke, the answer being “I T.” The name may not be the

longest of all placenames (that distinction is claimed for Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogococh

on the Welsh island of Anglesey or Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu

in New Zealand), but the city may be the one that has had the most

names. To tell its names is to tell its history.

“Constantinople

is a very long name; how do you spell it?” runs the schoolboy

joke, the answer being “I T.” The name may not be the

longest of all placenames (that distinction is claimed for Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogococh

on the Welsh island of Anglesey or Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu

in New Zealand), but the city may be the one that has had the most

names. To tell its names is to tell its history.