The Perseid meteor shower has long been famous as the most reliable of the year. Its peak comes in the night between August 13 and 14 though you may spot Perseids on previous and following nights. Here is the scene an hour after sunset, as the Perseids begin to shoot into view over the north-eastern horizon.

See the end note about enlarging illustrations.

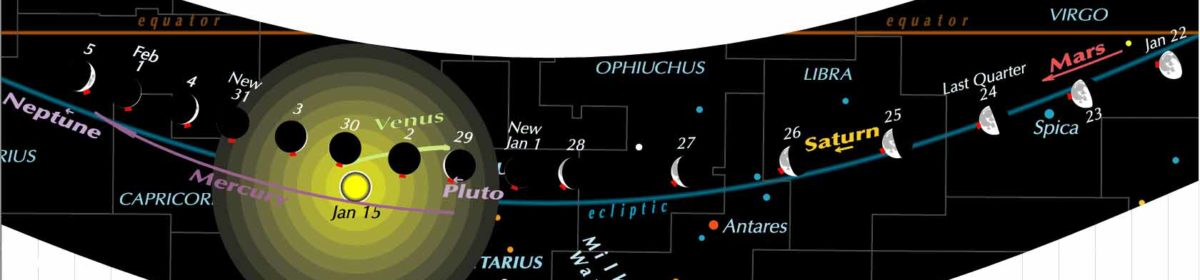

The meteors, traveling essentially parallel paths in the orbit of Comet 109P Swift-Tuttle from which they were shed, appear to radiate from the constellation Perseus – actually from the northern tip of that constellation, near to Cassiopeia. They can appear in any part of the sky, but if you can trace a streak backward to the region of the radiant, it was a Perseid and not a sporadic meteor.

This year is somewhat unfavorable, because the bright Moon, only about two days before Full, rises into view about the same time, and its light will drown out the fainter meteors.

As the night goes on, the radiant will slope up higher (parallel to the celestial equator), until in the hours before dawn it is almost overhead. Thus these meteors, like many others, are best seen in the half of the sky after midnight. Another and more explanatory way of putting it is that the meteor stream is meeting us from in front, so that the morning or front side of Earth is colliding with them – which is also why they appear swift as they burn up in our atmospher.

Despite the bright Moon, you can have fun on a warm evening, couting how many you see in an hour of these “children of Perseus.”

__________

ILLUSTRATIONS in these posts are made with precision but have to be inserted in another format. You may be able to enlarge them on your monitor. One way: right-click, and choose “View image”, then enlarge. Or choose “Copy image”, then put it on your desktop, then open it. On an iPad or phone, use the finger gesture that enlarges (spreading with two fingers, or tapping and dragging with three fingers). Other methods have been suggested, such as dragging the image to the desktop and opening it in other ways.

This past week in San Francisco we had four very clear nights in a row (accompanied by four very hot days, unfortunately). I was out before dawn with binoculars, finding Neptune, Uranus, and Vesta, reacquainting myself with the Hyades, Pleiades, and Orion, and greeting Mercury and Sirius once dawn had brightened the sky. I saw a few Perseids without even trying.

By the way, the time on the illustration is 8:60 pm. Is that the same as 9:00 pm?

I hadn’t noticed that 8:60 PM! It must have been a rounding from an instant that was nearer to the hour than to one minute before it; I’ll have to look into my program – tomorrow…

Yes, when I make the program tell me to ridiculous precision what “1 hour after sunset” happened to be at that chosen date and location, it tells me: 8 PM and 59.813331 minutes.

So, rounded to the nearest hour, it was 9 PM. But rounded to the nearest minute in the hour beginning at 8 PM it was 60.

The situation is like that of, for instance, Moon phase dates, which can fall close before the end of a Universal Time hour. We could round up to the next hour. But it wouldn’t be so simple, because the hour could be the last of a day, or even of a month, or even of a year, so I would have to elaborate the program to do that. Which some sources do, which is why they can give different dates for e.g. Blue Moons. I think it’s more interesting, besides less trouble, to leave it at “60 minutes” and explain why.

I don’t do any computer programming, but I do have an inordinate interest in time and timekeeping, so I can relate to the question of whether 8:59:49 pm is best called 8:59 or 9:00. For my own practical purposes I just round everything to the nearest five minutes, because that’s the shortest meaningful time span I can easily perceive without staring constantly at my watch. So everything between 8:57:31 and 9:02:30 is just 9:00, give or take a couple of minutes.

Coincidentally, just this morning I was figuring out when local solar noon will be on the September equinox. The moment of equinox will be at 0750 UTC 23 September 2019. 0750 UTC is 12:50 am PDT. We’re on daylight saving time, San Francisco is 2 degrees 25 arcminutes west of the central meridian of the Pacific time zone, and the equation of time will be approximately +7 minutes 30 seconds. Local solar midnight on 23 September will be at 1:02 am. Since the moment of equinox will be before midnight, I will consider 22 September to be the day of the equinox here in San Francisco. Climbing down this particular rabbit hole has no practical value, but I enjoy it.

My favorite meteor shower of the year. As always beautiful illustration too. Change the first word of the 3rd sentence to Here.

Thanks! Done.