Prose is linear, but the blog-and-comment system, like much in life, is non-linear and problematic to manage. Threads arise in the comments that want to squirm back out into the blog.

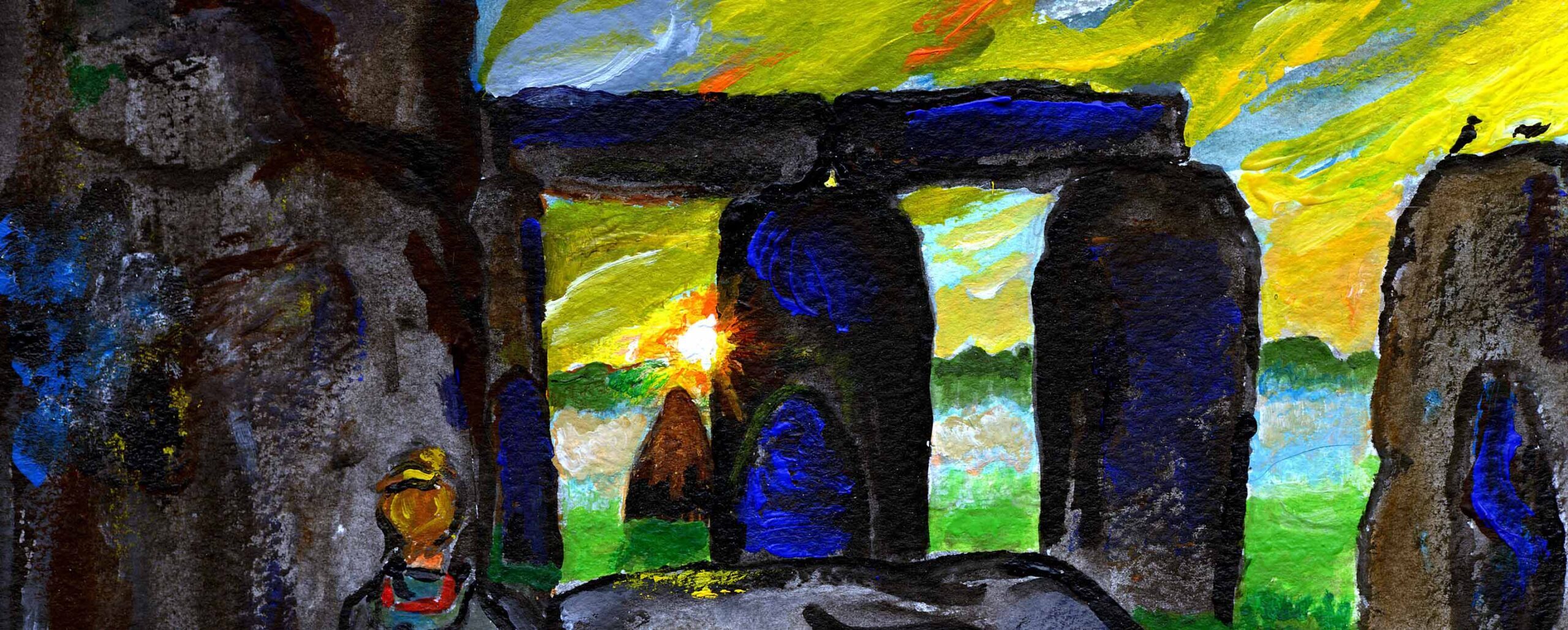

Left eye and right eye. A pair of pictures of the path of periodic comet 46P Wirtanen, now rushing up just outside Earth’s orbit. The cone-shaped arrows in Earth’s and the comet’s paths are at the end of 2018. The stalks from ecliptic plane to comet orbit are at one-month intervals. The grid lines on the ecliptic plane are 1 astronomical unit (Sun-Earth distance) apart. The Earth is exaggerated 500 times in size, the Sun 10.

George Moellenbrock, a radio astronomer, asked: “Have you ever considered generating stereo pair views of your visuals?”

I did, way back, build this possibility into my space diagrams. That is, every time one of those programs runs, it tells me a second viewpoint, for the other eye, 3 degrees (say) to the right. That enables me to run the picture a second time, with the shifted viewpoint. I showed some stereo pairs in the Astronomical Calendars of a few years. The caption for a 3-D view of Comet Hale-Bopp’s orbit said:

“Gaze perpendicularly between these two images, focusing beyond them so that they seem to be four. Then let the two central images fuse into one. This should have a strongly three-dimensional effect. No wonder: the viewpoints of your two eyes are 3° apart, which at a distance of 15 astronomical units means 0.785 a.u. or about 117,000,000 kilometers!”

The reason I didn’t do more of this was that the side-by-side pictures had to be small, otherwise the eyes simply couldn’t fuse them. And my eyes now doubt that they could fuse them at all.

But, George, let’s try it again. Will it be easier, or even harder, with pictures on a screen instead of on paper? Maybe you have more power of adapting a screen image, by making it smaller.

Use the same instructions – “Gaze perpendicularly between…” I’d be glad to know whether, for you, the 3-D effect clicks in.

My program told me to move the viewpoint from ecliptic latitude 15°, longitude 5°, to 14.98°, 8.11°, for the right eye. The viewpoint is 10 a.u. from the Sun, and nominally the eyes should be 20.833 centimeters from the paper, but don’t take much notice of that.

George added that “The past/future Earths views would seem to be perfect for this approach, and would really convey the concept well!”

I’m afraid not. For a moment it seems plausible: the chain of Earths, like beads on a string, could seem to stand out in front of the remote background. But those pictures are not of my “sphere” family; they are a type of charts. Can I explain this? They are not like views of a three-dimensional model at which you are looking, and around which you can sidle to get different viewpoints. They are like photographs of your surroundings. A horizon-based (altazimuth) chart looks outward from the location where you are standing. To make it stereoscopic – to make those Earths appear shifted against the background of the stars – you would have to have a second viewpoint, as if having your right eye hundreds of miles away around the Earth! I can’t at the moment see any way of recasting the program to be like that. And the pictures would be large.

It makes sense in real life. You can look out at space, with its near and far layers – clouds, meteors, planets, stars, galaxies – and know that they are at immensely different distances; But you can’t see those differences: you can’t waggle your head to make Mars waggle left and right in relation to Antares.

Another comment-thread was provoked by my new habit of appending to every post: “Cato ended every speech to the Roman Senate with: ‘Carthage must be destroyed.’ I want to end every message with: If you’re not doing something to slow carbon emission, you’re speeding the end of civilization.”

Not only is this annoyingly preachy, but it also is programmed: I’ve added it to something called a “macro,” which makes it automatic (though I can delete it). Yes, I’m inclined to be both programmed and preachy, and preaching only works on the choir. Anthony Barreiro is one of those who have the same understanding as I do of the now almost inevitable global disaster, and he commented:

“Just so long as we don’t destroy the carbon by burning it, as Scipio and his legions destroyed Carthage.”

Yes, Anthony, “carbon” in this context is short for carbon dioxide, which we need to reduce by emitting less and sequestering more. I had already thought of putting “Carbo delenda est” into my message, echoing Cato’s “Carthago delenda est.” Unfortunately the Latin word carbo, which meant burnt wood or charcoal, is masculine, so I ought to say “Carbo delendus est,” but I’ll be ungrammatical and stick with “Carbo delenda est.”

“Carthago delenda est” is, or used to be, a fairly familiar Latin tag – had you heard it before? As with many quotations, it became improved by erosion. The words with which Cato insisted on ending his speeches, on whatever subject, were not so compact; they were variants of “Ceterum autem censeo Carthaginem esse delendam,” which we could translate literally as “On-other-matters, however, I consider Carthage to be worthy-of-being-wiped-out.”

Marcus Porcius Cato was known as Cato the Elder or Cato the Censor. A censor was an official in charge of regulations, including building codes and public morality; politicians in the Roman republic often held this office and others on their way up to the consulship. Though it was one of the stages in Cato’s career, I assumed that the nickname “Censor” – actually, Censorius, “the Censorious” – stuck to him because he was such a stiff old conservative, hostile to all things new-fangled or foreign (such as Carthage) or lardy-da (such as Greek culture). But maybe it was also because of his tiresome ending of speeches with “Censeo – I opine that…”

His great-grandson, Marcus Porcius Cato the Younger, who had the family’s conservatism but in a more attractive form – the tendencies he disliked were dishonesty and corruption – committed suicide at Utica near Carthage, rather than accept the man who had made himself dictator, Julius Caesar.

When I was riding up Italy, I had many steep climbs to Italy’s hilltop towns. Somewhere in the hills south or east of Rome I came up to the gate of an observatory: it was called the Observatory of Monte Porzio Catone. I left my bicycle outside and went up the steps and in through the open doorway, but encountered nobody. I went up stairs and along corridors, and still found no human beings. Perhaps they were nocturnal. I lingered, waiting in vain for someone to appear, and passed the time by making this sketch of the marble stairway.

__________

This weblog maintains its right to be about astronomy or anything under the sun.

Cato ended every speech to the Roman Senate with: “Carthago delenda est – Carthage must be destroyed.” I want to end every message with: “Carbo delenda est. We must get rid of carbon dioxide. If you’re not doing something to slow carbon emission, you’re speeding the end of civilization.”

I believe the office of censor was only open to those who had previously held the office of consul. Thus, a censor would presumably be a person held in some esteem, like a senior statesman or professor emeritus. Just saying. . . . Cato may have been a mean-spirited xenophobe, but he had his admirers.

Hi Guy,

A good computer programmer writes a “black box,” a program, which consumes & generates well only what input & output data is essential to the program’s purpose. Writing prose or verse well employs a similar black box, the very words of the writer, his input and output data.

I share your take on carbon emission, so want your closing “Carbo delenda est” paragraph to operate on your audience as successfully as possible. For me that success means as widely as possible. You may not wish to be as inclusive of your audience. If so, ignore my advice & leave your paragraph as is. It carries with it everyone who has followed your blogs & therefore learned from you (from your auxiliary paragraphs) about the historical setting for Cato’s famous plea to the Roman Senate. I want the closing paragraph to succeed without your intervention; I want it to close without leaving any confusion in the mind of any reader. That closing paragraph, therefore, must, like a black box, achieve its purpose without comment from you via additional paragraphs. From that strict perspective, consider adding to the closing paragraph a few more words, but words also ordered carefully to leverage some rhetorical effects (parallelism, chiasmus, contrast) to facilitate their absorption into the hearts of your readers while they are learning any new Roman history they need that illuminates Cato’s Carthago delenda est so it might impress upon them the full weight of your sentiments about carbon emission. Suggested rewrite:

When Carthage became a rival to Rome for command of the Mediterranean, Cato the Elder routinely ended his every speech to the Roman Senate with the plea: “Carthago delenda est”—Carthage must be destroyed. I want to end my every message with: “Emissio carbonis delenda est”—carbon emission must be eradicated. Si tu emissionem carbonis non, festina lente, retardas, tu acceleras finem nostrum—if you’re not doing, as quickly as possible, something to slow carbon emission, you’re speeding the end of civilization.

Note the occurrence twice, back to back, of the parallel syntax: Latin clause in quotation marks, then emdash, then English translation. A 3rd like parallelism, but in variation, follows: your own Latin, italicized rather than quoted (Can that be done here in the blog?), then the same emdash, & then again your English translation. I’ve deliberately used Augustus Caesar’s famous saying, “festina lente,” make haste slowly, meaning carefully, since it seems especially apropos to your context, and belongs as well as delenda est to someone of your classical learning, who is here, obviously, deliberately wielding that learning to grease the delivery of your bias on a very important public issue. The chiasmus is in the 3rd parallelism: tu emissionem retardas (subject-direct object + verb) vs. tu acceleras finem (subject-verb + direct object). I chose emissio because it is feminine as carbo is not, & therefore saves you from breaking Latin agreement by using carbo, & because anyone can extrapolate “carbon emission” readily enough from emissio carbonis & emissionem carbonis. Also, the two-noun phrase “Emissio carbonis” does not seem to be a great enough multiplication of Cato’s single noun “Carthago” to detract at all from the rhetorical impact of “Carthago delenda est” when you leverage it for your modern “Emissio carbonis delenda est.” I softened the very strong delenda est the last time that notion had to be said by choosing retardas instead, since retardas continues your argument from the opposite extreme, not that of destroying carbon emission (an ideal to be wished for), but that of at least slowing it down (the practicality that most certainly can be achieved), which flatters your readers with the impression your mind is more balanced than to only shout at them from the ideal. And of course retardas contrasts perfectly with the quick succession of acceleras, & thereby emphasizes that acceleration. Finally, the genitive of the whole nostrum (of us) on finem (end) is also deliberate, as it emphasizes your “end of civilization,” the wording of which I very much want to retain, by emphasizing the nuance of what that wording actually means, “the end of us.”

John

TI appreciate the full thought you have put into this, John, and intent to refer to you next time I unburden myself of some “Points”. But I think it’s time for me to drop my routine ending, or at least that part of it, and instead occasionally put in a one-line fact that I’ve just read about the progress of climate thange.

“Emissio carbonis delenda est.” — Well done!

Guy, I like your idea of peppering blog posts with surprising and sobering facts about climate change. Might I also suggest including the occasional bit of good news? E.g. the recent Fourth National Climate Assessment found that, despite the federal government’s desertion from the field of battle, US states, cities, businesses, and individuals are doing enough to meet US obligations under the Paris climate agreement. It’s not enough, we need to do more, but it’s evidence that people care and are trying.

I agree, and am going to take this into account next time I get some “Points” off my chest.

Hello Guy-

I went back to my old copy of the Astronomical Calendar 1997 and found the lovely Hale-Bopp stereo. And I was thrilled to see the Wirtanen stereo today! Apologies to you for encouraging a squirmy idea, and to any of your readers for whom stereo views encourage a headache!

Actually, while I generally manage to “fuse” stereo pairs, I seldom manage to also satisfactorily focus them when “free-viewing” as you instruct. Achieving both simultaneously is a bit of a brain-teaser—physically focusing at one distance while perceiving depth and distance at others. And it seems to have gotten harder with age, alas. So, I usually use some sort of stereo-viewing aid, usually a modern, screen-friendly version of the traditional stereoscope, of which a range of inexpensive options are available online. These are often deemed a nuisance, but I find the stereo effect so compelling that it is worth it—and it vastly reduces the headache risk. And now that my eyes finally demand correction for reading—it really seems no burden at all. Viewing stereos on a screen is certainly no more difficult than it is on paper. It provides an opportunity to size the picture optimally, if necessary, and some may find the glossy screen an aid to disentangling focus and fusion.

The Wirtanen stereo is very nice, showing very clearly the inclination and course of the comet’s orbit and close, fortuitous approach to Earth. The scale of comet passages like Hale-Bopp and Wirtanen are especially well-suited to this sort of view: it is especially nice to see how their orbits lie at significant inclinations to the ecliptic, and how their positions relative to Earth progress. Two-dimensional views never seem to convey this well. There is one cosmetic oddity in the Wirtanen stereo, though: The Wirtanen text is at a different (closer) depth than the part of the orbit it otherwise seems to be riding on: the text in the right-hand view is shifted too far to the left. E.g., note the position of the ‘W’ in relation to the 2nd (from left) orbital “stalk”. This creates a bit of perceptual tension or conflict—different depth queues are suggesting different depths. A minor detail, except that the text is a large part of the view.

In my previous comment, I sniffed at the the ‘stalks’ and ‘grids’ used to help show depth in single views; actually, I find I quite like them here. They fill in what would otherwise be (and is!) empty space, and thereby enhance the overall 3D effect. In particular, the distinct spaces between orbit lines, stalks, and grid-lines (intended to make background/foreground clearer) further enhance the 3D effect, I think, through the creation of a sort of “contour illusion”, that to me, at least, gives the impression of transparent cylindrical columns and tubes. Had I access to your controls, I’d play with the spacings and thicknesses of the various lines.

Regarding the awkwardness of applying stereoscopy to the past/future Earths view, I take the point. Indeed, upon further thought after posting my comment, I realized that a very wide stereo eye-separation “baseline” would be needed to convey depth on the scale of Earth’s orbital motion over even just hours to days. And, more to the point—and I think this is your essential objection, beyond the particular logistics of your programs—the required baseline is decidedly impractical for any specific horizon view of the sort you’ve generated for past and future Earths.

On the other hand, we can, in principle, place the center of the stereo baseline at any location we choose, and through control of the separation of our virtual eyes, we can achieve the stereo view demanded by the scale of the scene. In fact, one might consider substituting for the current Earth an Earth-sized head with eyes nearly poles apart and looking out upon the ecliptic at a chain of ghostly past or future Earths. Or, ~equivalently, we could imagine our large head viewing the Wirtanen orbit as leaning in and tilting to rest a nose upon Earth’s equator and then peering over the limb towards its past or future. We would no doubt find we’d need to enlarge our head even more to perceive depth much beyond a few days fore and aft. Such is the vast range of scale even just between the size of our planet and the size of its orbit, and that is the lesson. Zooming out (a la Astronomical Companion) to see the whole solar system, the local neighborhood of stars, the whole galaxy, etc., demands ever larger heads, increasing exponentially.

Ultimately, I think the exercise here is not unlike the one you confronted initially with the past and future Earths: deciding how to draw them (how often, how big, etc.) to convey the point. The vast range of scale is quite the challenge here, and the exercise (at least for the programmer) is one of discovering this fact through experiencing it. Your views and descriptions have always been a fulfilling experience for me, and I think judiciously considered stereo enhances it. In any case, I find the present experience one of humility, not futility, and hope you do, too. Thanks again for your contributions to it!

Best (and sorry this comment got long),

George

Yes, labels in the stereo pictures: I deleted the lest they complicate the effect – but left one, the “Wirtanen”, so as to get opinions about it.

But it was a somewhat botched experiment: to make the pictures smaller, I had had to move both labels rightward from their programmed positions. This entailed also rotating them slightly, to fit the curve of the orbit. So the labels ended up in positions not calculated but just eyeballed. This will be why they were inconsistent with the stereo space.

The stereo effect uses parallax: shift of something’s position as viewed from a moved viewpoint. Parallax is how the distances of stars are found, but those are tiny parallaxes, very small fractions of a degree, obviously indiscernible to the human eye. But there is one astronomical object near enough to have a large discernible parallax: the Moon. It’s not, of course, a parallax discernible by moving your head, but by looking from places far apart. In the last few Astronomical Calendars I put small charts of the Moon’s travel over one sample day – with two positions for each time, one from a North America location and one for (roughly) Australia and New Zealand. So just possibly I might think of a way to do some sort of stereo diagram for the Moon. But not yet, too much else…

Guy-

Ah, yes! Thanks for emphasizing that the mechanism underlying stereo views is indeed geometric parallax, the manner by which professional astronomers can _directly_ measure _geometric_ distances to astronomical objects. This is so-called “annual parallax”, and distance measurements are achieved by making observations six months—and 2 AU—apart and looking for the apparent position shift of nearer stars against the much more distant background. Long and skinny triangulation. From Earth’s _surface_ (and not accounting for location in our orbit), indeed, only satellites (including artificial!) and meteors are close enough to exhibit discernible parallax, yet I’d add to that list at least a few hours worth of past and future Earths! And, alas, longer-than-trivial instantaneous parallax baselines (the spacing between viewing points) are needed, especially if you want to discern the spherical shape of the moon in addition to just its distance. I.e., the relative parallax between the front of the moon and its limb is less than 0.5% the direct parallax corresponding to its distance. In other words, you need a parallax baseline capable of measuring*** a distance more than 200X the distance of the moon to convincingly and directly discern that it is a actually sphere and not merely a disk. Again, the difference in scale is a challenge! Motion of the moon in its orbit (including libration) and of our platform as Earth rotates can help if we are willing to wait between snapshots. I think the diameter of Earth is only just wide enough to discern the spherical moon via parallax.

That the moon is tidally locked to Earth and thus consistently shows only one side to us is an unfortunate fact of physics, and one that perhaps encouraged the casual impression through history that it was only a disk (the appearance of the moon’s phases being a somewhat more subtle clue as to its true 3D shape). One wonders if a distinctly and evidently rotating moon might have helped the ancients better (and sooner) understand the true shapes and nature of bodies in the solar system…. In this regard, the view of Earth from an outpost on the nearside of the Moon must be so much more impressive: From a spot on the Moon, Earth will always hover in the same place (owing to the tidal lock), will be distinctly larger and brighter and in vivid and variable color, rotate discernibly in under an hour, and display the (Earth-)monthly (==”Moon-daily”!) sequence of familiar phases as the sun swings around—and sometimes passes behind it, as we expect it to do on January 21! Images like “Earthrise” from Apollo 8 (50 years old, this month) tease us as to what this view would be like, and I am sorry that Apollo and our other lunar explorations haven’t provided a dedicated camera for this purpose. Apropos other sentiments on this thread, I think we might appreciate Earth more if we had regular and continuous access to such a view…..

***I realize that the statement “capable of measuring” is perhaps a bit subtle here, and depends on context. For conceptual astronomical renderings of the sort you make, of views of the night sky or planetary and cometary orbits and similar, “capable of measuring” should be read as “capable of rendering with adequate resolution”. This means adequate DPI to resolve the stereo/parallax effect for the relevant objects and the chosen stereo/parallax baseline, and over the field of view selected for the rendering. Wider fields of view will be limited in their effective “distance reach” through stereo for a specific choice of DPI. These considerations probably place fairly tight constraints on long chains of past or future Earths since they will demand a wide field of view as they swing around the ecliptic….

For “professional” distance-measuring efforts, “capable of measuring” means “having adequate angular resolution”, which is determined by the resolving power of telescopes (wavelength divided by effective diameter of the aperture), a well-behaved atmosphere (or none, by going to space), finite measurement accuracy, and subjects which are small enough (at their distances) to permit a reliable measure of their position on the sky with precision smaller than their parallaxes (stars are fine, but large, fuzzy objects like nebulae do not generally qualify). Optical astronomy from the ground is limited to parallax distances of only a few 10s to maybe 100 parsecs; equivalently, annual angular parallax measurements no smaller than a few 0.01 arcsec (and generally considerably worse). This captures only the very near neighborhood of the Sun, a tiny fraction (~1.2%) of the distance to the center of the galaxy, which is ~8300 parsecs. Even when we go above the atmosphere, interstellar dust substantially obscures our view within the plane of the Milky Way and we can’t see much further than perhaps a few 1000 parsecs. Turns out, radio telescopes can see through that dust, but have a more limited population of discrete objects to look at: Stars are generally invisible in radio (except for transient flares, decidedly inconvenient for repeated observing over many months), and so we observe masers—the naturally-occurring and very compact microwave/radio wavelength analogues of lasers often found in star-forming regions, and which should trace the spiral arms. The longer wavelengths of radio light, which nominally reduces angular resolution for ordinary single-dish radio telescopes to a similar (at best) resolution as ground-based optical telescopes, is more than compensated for by forming interferometers between very widely-spaced radio-telescopes and thereby realizing synthesized apertures that approach the size of Earth (or even larger with radio telescopes in orbit!). With these instruments radio astronomers achieve annual parallax measurements with precision down to a few 10s of _micro_-arcseconds, corresponding to accurate distance measurements out to several 10000s of parsecs. This enables mapping the whole of the Milky Way galaxy! Such mapping projects in both radio and optical are, in fact, currently ongoing….

Best,

George

Thanks for all that strict science. I’m especially struck by the possibility that, if the Moon visibly rotated instead of keeping one face toward us, people would far earlier have understood that heavenly bodies are spheres.

I did see the 3-D image with my eyes about 20 cm. from the screen but it was blurry since my near point is farther than 20 cm.

I’ve noticed what you mean about the threads/comments getting scrambled. This should help your blog readers: If you want to comment on an existing comment ,click the blue reply box below that existing comment, and your comment will be placed UNDER that existing comment. If you want to send a comment about Guy’s post that is unrelated to the existing comments, then type it in the box below “Write a comment”. It will then be placed ABOVE the other thoughts.

I’m sure I’ve read “Carthago delenda est” somewhere before, but I did an internet search to find it again. Likewise Wikipedia told me Scipio commanded the Roman attack on Carthage.

I’m hopeless at stereoscopic pictures. Either they don’t work for me or they give me a headache.

Reading this on my phone, I doubted the three d effect would work – thinking the small screen would interfere with allowing eyes to align. Wrong. Took a bit more deliberate concentration than with larger printed 3-D images, but effect was clear.