This wild event, which is the traditional way of celebrating Guy Fawkes Night at Ottery St. Mary, has been on my calendar ever since I heard of it a dozen or more years ago. But it was twenty miles away, we couldn’t get there without a car, and it might be banned for reasons of safety before I could ever see it. But see it I did, last night, taken there by kind neighbors Liz, Tess, and Martin.

I had been by daylight in Ottery, in the valley of the River Otter in east Devon. It has to be loved for being the birthplace of Coleridge; his father was vicar of its great church of St. Mary, which is in Simon Jenkins’s Thousand Best Churches of England.

Almost all of the roads and lanes through the countryside around Ottery were closed, and consequently solid with cars, all inching forward in the dark till they could get to where they were blocked by barriers and officials and could turn and start inching back; the officials’ voices were hoarse from repeating their directions for finding the road that did lead in. We could already see distant smoke when we at last got to a vast field reduced to mud by an ocean of cars. I trusted my friends to memorize the way back to their car. We traipsed with the traipsers for most of a mile, passing the town’s bonfire and many gaudy stalls selling food and liquor.

And into streets jammed with people. How many? – how can you count a crowd that packs, from wall to wall, a network of irregular old streets? The only time I’ve seen a simple way to estimate a crowd was in the plaza of Cuzco in Peru, at a mass for victims of an earthquake: by working my way along two sides of the square and roughly counting I could multiply (my answer then was 80,000). We guessed 600 cars in the field, and there were three other car parks, and the average in a car may be three, and the town’s population is 7,000, so a guess is 14,000. And there must have been at least a hundred yellow-jacketed stewards and police.

Each car pays ten pounds, and every stall, shop, and pub that is open does a thriving trade. Burning Day has become a tourist magnet, on which Ottery surely now depends.

The crowd was threaded by streams of people in contrary directions, trying to get to some spot they thought advantageous – families clutching each others’ pigtails, actual or metaphorical, in fear of getting separated. Which, indeed, was my only fear; if I’d lost sight of my friends I’d have languished through the night among inebriated revellers.

I thought I discerned an avenue through the crowd, along which the barrels would come, but there was no avenue.

Ah, a barrel-lighting! Flame roaring up; but it came out of some opening of the crowd that was twenty body-depths away; we (or the taller among us) could see the flame but not what was happening underneath it. I could see down into the opening only by raising my iPad like a periscope – it was part of a forest, above the crowd, of arms with smartphones at the tops of them.

The flame, to applause, moved away along the street. – And suddenly was coming back! and we had to scramble out of its path.

One time, trying to get you a photo, I nearly didn’t scramble back in time; I was grazed by the heat and sparks. The only moments when you could see the action clearly were the moments when you were having to scramble away and being knocked by other scramblers.

This took place in what seemed like a town square, or at least a widening in a crook of the streets, and I now had the notion that each burning would be in a different square. But some were just in stretches of street. There were eddies of movement in different directions on different theories, and then long waits for something to happen, and some burnings seemed to be simultaneously imminent in different directions.

You were pinned by shoulders; you tripped over objects on the invisible ground, some of which were planks, the ruins of barrels. The most likely thing to trip on was the curb. You could get onto a sidewalk and be in relative safety and with a slightly higher though more distant viewpoint, but when the crowd scrambled backward its heels met the curb and it fell into your lap.

In the din, we were engaged in conversations by a few informative locals. One wiseacre was giving his tips for surviving: “Keep your eye on the barrel… Bend at the knees like a monkey… I’ve seen all this twenty-nine times.”

I should have researched in advance to understand what was happening. My vague notion had been that men roll down a hill inside burning barrels. This must have been a cross with what I was told about Lyme Regis by one of its natives, that – until it was banned – the lads used to roll each other in barrels down Broad Street and into the sea.

What actually happens in Ottery is that a barrel is coated on the inside with tar, which is set alight, so that flame spews out of its open end. Later, through both ends and the joins of its planks. It is set into a harness on the shoulders of one man. Stooping under it, he runs through the crowd – in any direction. And back, and again, along different paths. Until, presumably, the barrel falls apart.

Each barrel-run starts at one of the town’s remaining pubs or one of the many former pubs – there once were twelve. Each successive barrel is larger, and the seventeenth and last – which comes at midnight and which we didn’t wait to see – is the giant barrel.

The barrel-carrier is helped by half a dozen supporting men, and this team – to some extent – keeps barrel and crowd apart.

The barrel-runs by the men were preceded, before our arrival, by milder ones by the children and the women. All barrel-bearers have to be born in Ottery St. Mary, or to have lived in it most of their lives. The children of Ottery practise in school, looking forward to their barrel-bearing adulthoods.

And the young Samuel Taylor Coleridge, did he ever run with a burning barrel on his back and did the weight and the fire emerge in any image of his poetry?

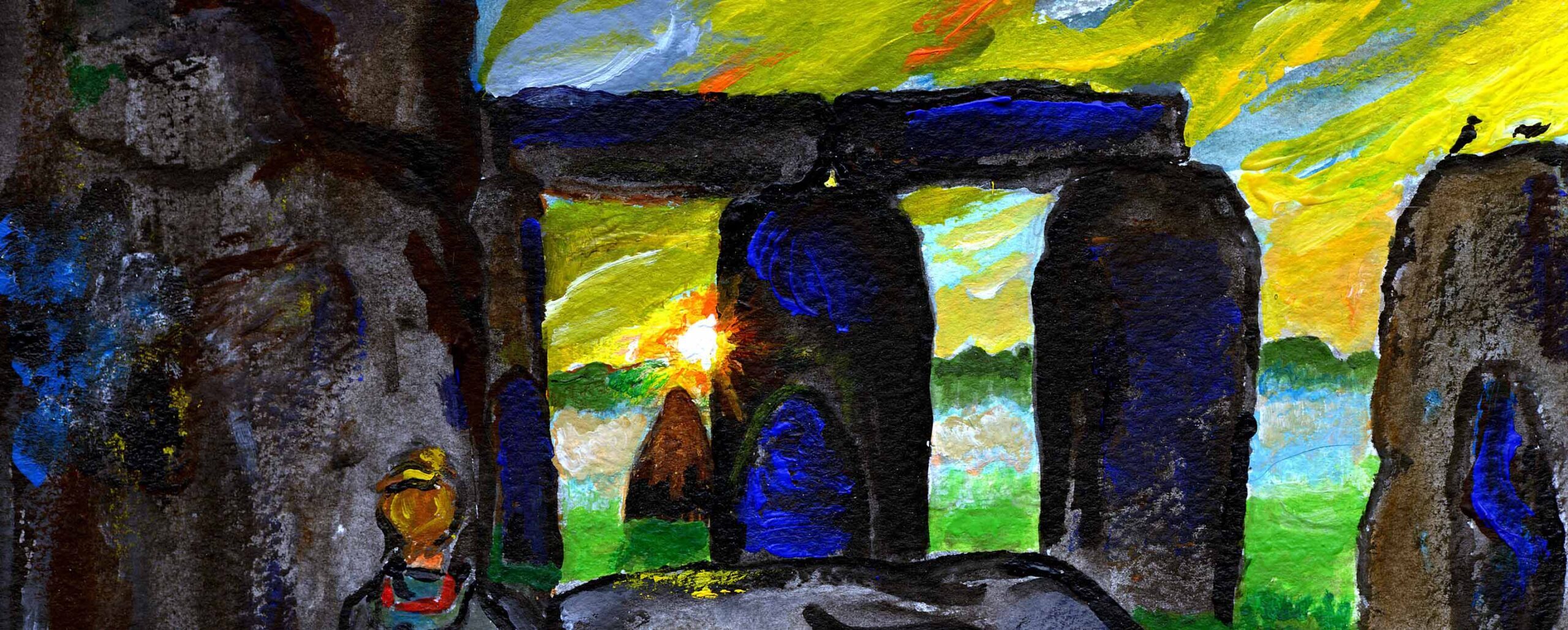

The barrel-burning is only one, though surely the most spectacular, of old English fire festivals. Though it dates from the seventeenth century, it and they and the Guy Fawkes bonfire and Halloween all surely trace further back, to pre-Christian ghost-rites of the dying year.

The tar used was presumably some of that produced for tarmac, but perhaps in the seventeenth century it was made from local pine trees. Archaeologists have recently discovered in Swedish forests large pits that they believe were tar kilns, from as far back as the seventh century. In them, pine was roasted slowly so that its resin became the gooey substance called tar, and this was used for waterproofing the longships of the Vikings, and this enabled them to plunder so many coasts of Europe, and colonize Normandy and England and Ireland and Sicily and reach Byzantium, as well as Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland – wherever in North America that was.

Why do you not own a car? Is it so you don’t burn fossil fuels?

That’s the best of several reasons, but I haven’t always been a purist. I learned to drive late; when I had to drive (a van) it was mainly because I had to take loads of Astronomical Calendars to the post office. I usually managed to do at least twice the number of bicycle miles as car miles per year (6,000 / 3/000). My last car failed its test and was sold as scrap for a pittance. I’m very glad to be without the annual paperwork.

Thanx for the response. I wasn’t being nosey… I just searching your mind for nuggets of wisdom.

Having a car is convenient but it would be nice not having to deal with maintenance, registration, and car insurance.

I prefer to use my bicycle if I have time and the weather is dry. Many times I just jog (in all weather). An urban trip that takes 10 minutes in my car takes 25 minutes on my bicycle, or 45 minutes if I jog.

Many city dwellers don’t own cars. Some Amish sects don’t drive cars because they say it breaks up families. Some psychologists say driving is stressful because the human mind is not equipped to handle the ever changing scenes at 100 km./hour, though I find driving relaxing.

A study has just shown that drivers in cities are exposed to levels of polluted air far above EU maxima (cars act as pollution traps), walkers too unless they take byways, cyclists the least, partly because they can overtake stationary cars so that their average times are shorter, partly be3cause exercise offsets pollution. The study was done on X thousand people’s journeys to work in the city of Leeds. It was in yesterday’s Guardian, I don’t have the link.

I walked hundreds of miles, barefoot. In another phase I lived in a van.

I’ve talked to barefoot backpackers who say it makes them walk slower and this makes them more aware of their surroundings so they enjoy nature more. Don’t know if I’m ready to do that though.

Here’s a cycling tip. I installed a rear view mirror on my bicycle. It is a high quality rectangular mirror made for a motorcycle. I can see if traffic is coming behind and if the road is clear, I ride closer to the center of the lane. This cuts down my transit time because I can go full speed (as opposed to riding on the edge of the road with its cracks, sewer grates, litter, and gravel.) I used your idea of taking pictures at an angle so that you could fit more content in the photograph; If I swivel the mirror 45 degrees I can see more behind me.

I would like to see bicycle freeways. They could be built much cheaper than a freeway for autos because of course they’ be less massive. Concept could be the same – limited access, passing lane, emergency shoulder. More people would ride to work or play. I don’t think a bicycle freeway would be practical for distant travel. A city 120 miles away that you could reach by car in 2 hours would take at least 6 hours on a bicycle.

I find no mention of this practice in the Coleridge biographies I’ve consulted, and can’t think of anything appropriate in the poems, but I would welcome correction on this. However, it may be relevant that on November 5th, during his schooldays, Coleridge would have been away as a boarder at Christ’s Hospital in London.

Wow, interesting. Hope you all had a good time

I’ve never heard of any credible evidence that the Vikings reached Virginia. Maybe you were thinking of the “Roanoke Colony, also known as the Lost Colony…the first attempt at founding [in Virginia] a permanent English settlement in North America.” L’Anse aux Meadows (in Newfoundland) “is the only confirmed site of a Norse or Viking settlement in North America outside of the settlements found in Greenland.” [all from Wikipedia]

You’re right. I’ve changed “Virginia” to “Vinland – wherever in North America that was”.