|

The beginning is almost an avenue, a broad gravelly path past a lawn. This is the sight of it with the early morning sun coming through:

PICTURE: from our stair window

(The stooping figure is collecting dandelion flowers and leaves, to feed the forty rabbits he keeps at his house a mile or so away in Yawl. He told me that the rabbits like dandelions, but buttercups, bluebells, and primroses are poisonous for them.)

Then comes a narrow bit between garden hedges, then the path runs on along the left side of The Glen, full of tall trees, with the river at the bottom. The path can be muddy, and is beset by beds of wild garlic that flower odorously in spring.

It comes to a road — the Springhead Road — which dips across the valley, pinched by the narrow stone bridge that you see to your right. On the left is a hamlet consisting of a low rambling old house (formerly Waterside Cottage, now called The Roost) and a few others gathered above it.

Beyond Springhead Road the riverside route continues as Mill Lane. You can touch the thatched roof of a cottage on the right (Brookside), and of another farther along (Pitt White), because they are perched down the slope toward the river.

The lane dwindles to a path and seems to end by running in through someone's front gate; but the path is the slit that dives sharply to the right down a rough little ravine. Again in deep woods, it runs along only two fathoms above the river; it must somewhere cross or coincide with the course of the leet, the former channel that used to conduct water along the valley side. The path scrambles back higher; there's a skyline quite close up to the left, a little too high for you to see over it into the open field. And now the path makes another and longer rough narrow descent in a veritable tunnel, foliage crowding overhead. (Here during the foot-and-mouth-disease outbreak of 2001, when all paths were closed, the way became blocked by nettles and brambles, and the first new walkers had to hack their way through.) The narrow bank on the right divides the path from the channel of the leet.

At the end of the wood, the path twists right — crossing the filled-in leet, whose stone sides show in the ground — and brings you down beside thatch-roofed Old Mill (also called Upper Middle Mill). One of nine mills along the Lim, it still looks the part: across its end stands the great wooden wheel, of the “overshot” type — water from the leet turned it by pouring into its succession of buckets. The wheel is a restoration lovingly made in 1968 by an old craftsman named Gapper (as recounted in a chapter on the mill by David Mostyn of the owning family, in The Book of Uplyme by Gerald Gosling and Jack Thomas, 2004). From the wheel's foot the tailrace water departed by the ditch along the side of the mill garden. The mill is built into the hillside; inside its rear wall is a second wall, so that groundwater can drain along the passage instead of into the interior. Parts of the thatch were said, by “a heritage mill expert,” to date all the way back to the mill's origin in the fourteenth century. This was a flour mill, and operated until just before World War One. The machinery remains in the granary behind the wheel and the kitchen below. The smaller building alongside was the bakery.

Some of the current residents may come to the fence and allow you to scratch their noses: a family of tall brown goats, who look as if they understand your remarks and could overleap the fence if they cared to.

You enter the first bit of flat ground since above Uplyme. The path meets another from around the other side of the mill: it comes, accompanying a stream, from the Harcombe valley, and is a route along which we sometimes cycle, bypassing the uncyclable parts you have just walked. The stream comes out of a valley that reaches northeast and north to Penn. In fact a contour map shows that the point we are at is the real gathering-point of the valleys that radiate inland of Lyme.

The combined path now crosses the river — still only a stream itself — on a small wooden footbridge. At this bridge you cross not only the Lim, but the boundary from Devon into Dorset. (Actually the river isn't the boundary, the bridge is: the boundary lies across the river, along the bridge.)

This seems to be the bridge in Beatrix Potter's drawing on page 38 of her Tale of Little Pig Robinson. The timid and nearly ill-fated young pig is trotting across it with the basket of eggs, daffodils, and cauliflowers that his aunts Dorcas and Porcas have sent him to sell in the market at Stymouth (a seaside town that seems to be Lyme Regis blended with other Devon seaports). The angle of stream to meadow is different, but at the meadow's back can be seen a thatched house that has to be the mill, without its wheel.

From the end of the bridge you step down into a kissing-gate. To get a bicycle through this kind of gate you have to hoist it on one hand to head-level, if it is light enough, which my mountain bike with its five attached bags certainly isn't; or stand in the middle and plan several heaves onto and over the farther fence; another way, barely feasible, is to erect the bike on its rear wheel and walk it through, like a horse on its hind legs. I thought I had quite a tough time negotiating this gate, until I met someone there with crutches, a baby carriage, and a dog that twined its leash around legs, wheels, and crutches.

(Update 2009: the kissing-gate is no more: one flank of it having been removed, it is an ordinary easy gate.)

Now you find yourself — along with three horses or a dozen curious heifers — in a large grassy field, known as Bumpy (or, in other local mouths, Bumpety). The name really applies to the half that swells up in front as you extricate yourself from the gate. In snowy winters the population of Lyme turns out here for tobogganing. The broad slope with its considerable ripples and troughs gives a long roller-coaster ride to many toboggans at a time. The name could be Slumpy, because those ripples and troughs are surely examples of the land slippage so prevalent in and around Lyme.

PICTURE: toboggan

The farm up to the left, Haye Farm, was formerly called Land of Promise.

The larger half of the L-shape of “Bumpy” is flat, and you may follow the vague path along the middle of it or venture aside to look at the river's tree-lined wanderings.

The end of the field becomes muddy where all footsteps converge on another kissing-gate, one that is less charming, because made of metal, but somewhat easier to get a bicycle past, because of the stile beside it. (Update: this kissing-gate was replaced in 2005 by a regular gate.) Inside a wood, the path uses two bridges to cross back over the stream — or, rather, a confluence of two streams, with much more water than under the previous bridge. Upstream to the left are stone terraces at the foot of a former farmhouse.

Someone told me that the farmer used to go around the town with a yoke over his shoulders and two buckets, from which he sold milk; and was one of the first in the country to have recordings of classical music playing in his cowshed, to increase the cows' productivity.

The path, now again on the river's left bank, runs beside a flat field which used to be hopping with rabbits (news is that they've died of myxomatosis). This is the last rough-and-narrow part of the path; it presents only one more obstacle — a prodigious puddle — before delivering you to a roadway so smooth and quiet that it might have been made for roller-skaters; it's certainly a relief for you after all those muddy and stony places. Actually it's smooth and quiet because it was laid recently and is just a service road to Lyme's sewage works. It leads through the woods until it comes to a crossing with another road. And here Lyme Regis begins.

The way you've come is remarkable. The ordinary way from Uplyme to Lyme, the road — which lies higher along the hillside — has become built up enough that the two places are almost one. Yet there is this alternative way along the river. Setting out from Uplyme, you've gone by woods, ravines, stiles, bridges, a broad meadow, more woods — and quite suddenly you enter the ancient small town by its back door. It is a reminder of how the world was, a century ago, when Uplyme and Lyme were distinct places, spaced apart by deep green country.

It was on taking this walk, in the last minutes of our December visit, that I exclaimed: “That's it — we've got to live here!”

The impression continues to mount. The road you cross is Roman Road; on your right is Horn Bridge. You follow a road (or is it just a path?) like a ledge along a reach of the river almost hidden under the branches of trees; squeeze past another former mill; across another road; a place where the river dodges away from the route, then reappears around a garden wall; and a short lane called Jericho that ends by diving into the river! A footbridge; a small waterside park; the river takes itself out of sight now to the left; a lane that rises, curves, and redescends, set with cottages in pastel shades. It is about here, as a small plaza opens down ahead, with a pink-painted pub called the Angel beside it, that I get the feeling that the town is a toy town.

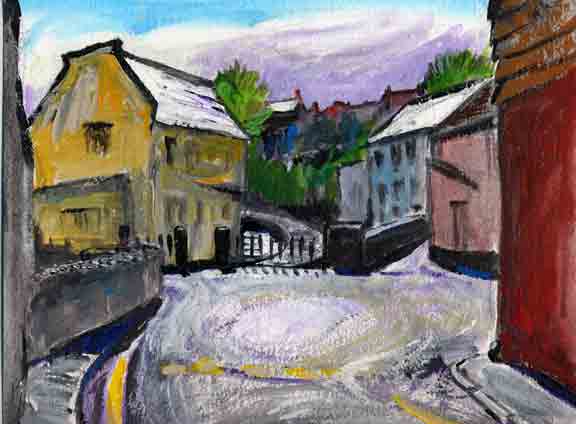

PICTURE: view down Mill Green to plaza ]

All along this walk you have kept guessing which turnings to take — which is supposed to be the East Devon Way? — by roughly following the river. Now another lane closely walled by cottages aims left across another bridge, and you go that way. (Saving for another time the discovery of a yet more improbably pretty version of the route, through a gate in the middle of the bridge. Or possibly the path on the river's right.)

You are now in Coombe Street. After a little more than a hundred yards a vista opens to the left up Monmouth Street to the tower of the town church; but Coombe Street (now one-way and in the contrary direction — lucky for you you're not in a car) narrows, gives a final very narrow twist, and suddenly—

Coombe Street spits you out into the main street, among strolling holidaymakers and hurrying Lymians, and vehicles cautiously sliding among them. You're in the middle of the town, and already you can sense the close presence of the sea. (It even shows through a shop window opposite.) Up to the left are quaint buildings, the museum, the guildhall. But, drawn by the sea, you turn right, cross one more bridge (with limestone parapet and glimpse down to the river in its last deep trench), and within a few yards— |