The Lyme Maze Game

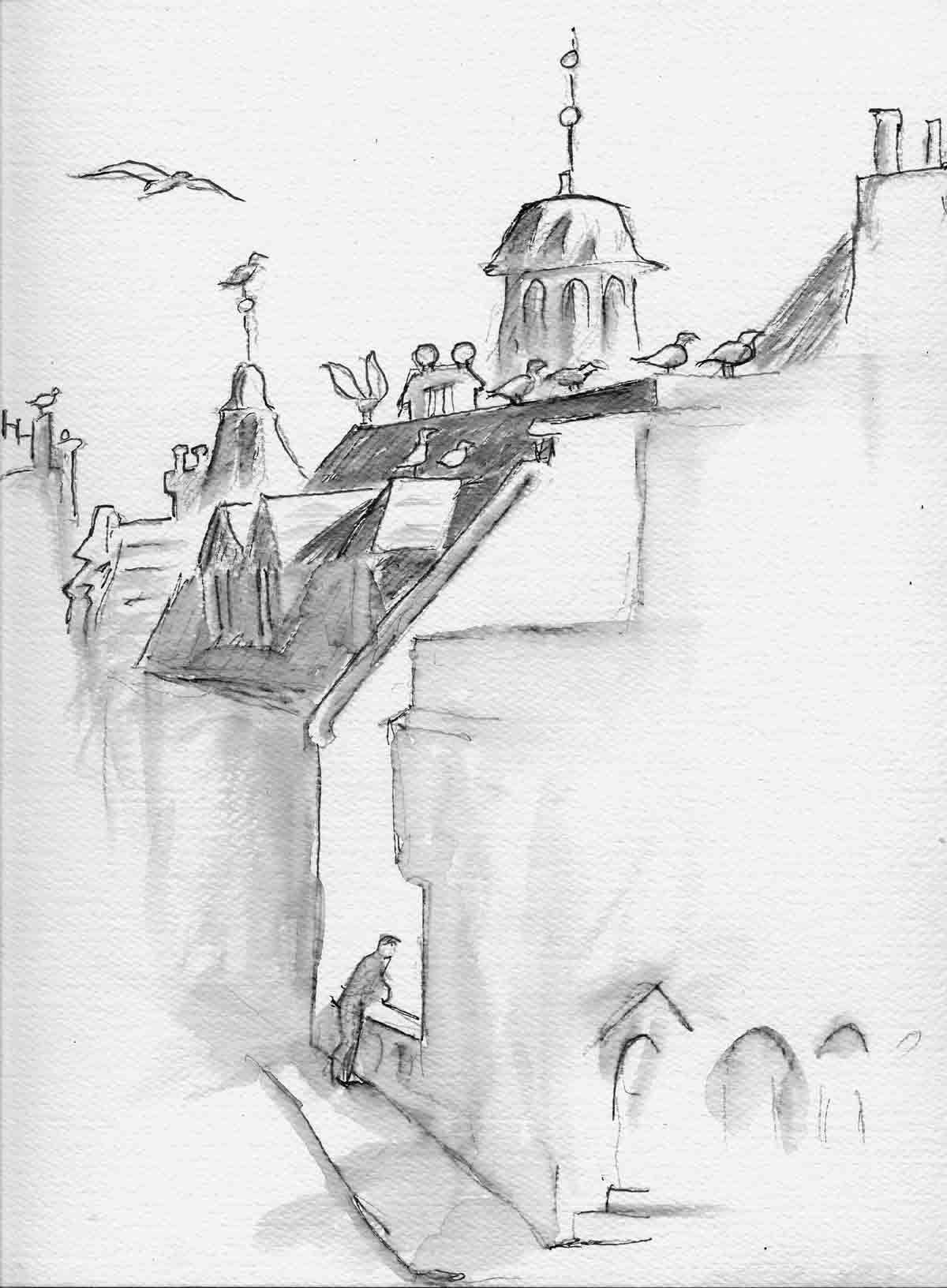

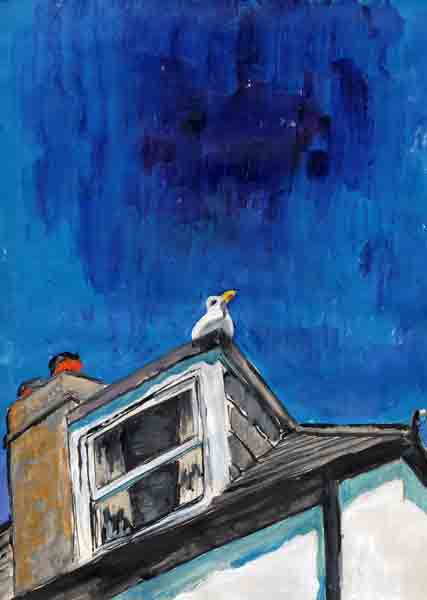

PICTURE: gulls in air Gulls are an element. A seaport consists of town and people, water and craft, air and gull. Settled on the abundant substitute cliffs that the town provides—roofs and chimneys—the gulls on their sturdy legs look comically conspicuous and interruptive; the skylines are punctuated by stalked blobby excrescences, some of which prove to be ornamental urns, others gulls.

(And the occasional kite tethered in a steadier-than-usual southwestern wind.) As they take to the air the gulls immediately shed this stolid inharmony. From our own perch on the Bell Cliff, the airspace before and below, between us and the Rock Point Inn, seems to me sheared into glassy layers; the gulls themselves are expressions of the surfaces in the air. Above us, a gull hangs motionless in the wind, yellow light pouring through the ailerons of his wings, before letting the wind snatch him dizzyingly away. At certain times of the day, or more probably states of the tide, the gulls roost companionably on the sea outside the river mouth, or wait on Broad Ledge as it becomes exposed with its harvest of food; at other times they work the tourist crowd. A cloud of gulls as numerous as midges floats just above the human layer, ready to drop among its feet and remove its edible litter. But gulls are never all in one place; they are at their posts on lamps and banks and chapels as we go up the street; any time we look up from our garden there is at least one gull gliding over; the same at Taunton or any place thirty miles inland. The gull-scream, and their other noise, the "laughing" ("hak hak hak!"), mingles with the quarrelsome cawing from the rookery.

Gulls' elegant outlines in the air seem simple yet are elusive to grasp for a sketch, since they are constantly folding over from one outline to another. On Bell Cliff I can study them more closely—the position of the nostril and orange patch in the yellow beak, the fixed smile where the beak meets the cheek, and the plump firm surface of the plumage (every gull seems packed out with health)—because a gull or two arrives to stand between the railings. But the main beggars on the Bell Cliff are pigeons; there is also our friend the starling, who eats from our hand. Pigeons at certain times burst in a crowd of hundreds from among the buildings; they live on ledges in the artificial canyon of the river. PICTURE: pigeon squadron] Some humans have become too civilized know how to share their living-place with wild things. Anti-gull notices are posted by the civic body (there is one right underneath the Bell Cliff): Seagulls are encouraged into the town by being fed. They cause nuisance by noise, excrement, ripping open refuse sacks, and can display aggression for food. Please refrain from feeding the gulls. Luckily gulls are too tough to be discouraged. A friend says "It's a pity gulls are such unattractive birds." (I find them faultlessly beautiful.) Another friend, seeing a gull out of the window, says "Got your gun?" He explains that a pair of gulls that morning, as he was trying to knock down their nest and chicks, divebombed him with excrement. A letter to the local paper: "Heavy culling of gulls is long overdue . . . The infestation has reached epidemic proportions . . . One lonely widow actually feeds the foul predators [sic] . . . Their screaming and shrieking keeps us awake . . . These noisy and dangerous predators detract from the quality of life in these otherwise idyllic coastal residential neighbourhoods . . . " Perhaps Ian and Linda Lowis of Charmouth should move to Malta, where they could take part in the annual massacre of birds migrating from Africa. Schoolchildren aged eight are applauded for their "environmental" project: they polled the public on which kind of gull crime is worst (spoiling cars' paintwork has the edge over "swooping on the beach for food") and which is the best anti-gull measure: nets, nest-destroying, or culling. (Culling, in case you weren't sure, translates into English as "killing".) Why do people who hate seabirds choose to live by the sea? They remind us of the townies who buy houses in the country and complain of the smell of farming. Gulls are despised (like vultures and dung-beetles) for their willingness to scavenge our garbage; loathed (like rats and flies) for their chutzpah in thriving among the most destructive of "predators", man. One species, the greater black-backed gull, does kill other birds. A bit more about gulls—

|