|

Britain's counties (county is the Norman-French word, shire the older English one) are not like the myriad administrative counties into which American states have been snipped: they are the ghosts of ancient realms, with varied origins, sizes, and characters. (I'm using the present tense; as will be seen, it ought partly to be the past.)

The names of a few date back to pre-Roman tribes: Dorset (from the tribe called Durotriges), Devon (the Dumnonii). The Celtic Britons maintained their identity for several centuries more in Cumberland (land of the Cymry or Welsh) and up to modern times in Cornwall (Kernow in its own Celtic language). Celtic words survive also in the Berk of Berkshire (it meant “hilly”) and in Kent (the land of the Cantii, possibly meaning “coast”).

Then came the Germanic invaders, from tribes called the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.

The Jutes, though they came from farthest north (Jutland or northern Denmark), set up southerly kingdoms in Kent and the Isle of Wight.

The Angles (from where Denmark meets Germany) settled in the north: northernmost was Northumbria, their kingdom “north of the Humber,” of which the county of Northumberland is only a relic. A part of Northumbria “west of the moors” became Westmorland (its dialect is “Westmerian”). Other kingdoms of theirs were East Anglia, which divided into Norfolk and Suffolk; and Mercia, which covered the whole of the Midlands and has left its name to no county.

The third Germanic people, the Saxons, left their name in Essex, Middlesex, and Sussex; Surrey (“southern realm”) was another of their kingdoms; but the West Saxons had the most room to spread — as far as Devon — so that the kingdom of Wessex (which eventually gave rise to the kingdom of united England) was divided, like Mercia, into many earldoms that later became counties.

Most of the remaining county names come from towns. Bedford is the county town of Bedfordshire, which is abbreviated as Beds. This is the nearest there is to a general rule, and there are fewer other examples (Worcestershire/Worcs, Staffordshire/Staffs, Yorkshire/Yorks, Hertfordshire/Herts) than there are exceptions. You can't add “shire” to the counties that end in “sex” or “folk” or “land,” or to Kent, Surrey, Cornwall. (Some say you shouldn't add it to Somerset, Dorset, or Devon; but older books do, and there is certainly such a thing as Devonshire cream.) You can't drop the “shire” from Hampshire, Wiltshire, Berkshire, Cheshire, Lancashire. Durham's county is not Durhamshire but County Durham. Some old towns, such as Warwick and Lancaster, long ago ceased to be the capitals of their counties; who remembers that Wiltshire was named for Wilton (itself named for the little river Wylye, and now almost a suburb of Salisbury) or that Somerset was the district of the “settlers around Somerton”? The names of Chester, Lancaster, Southampton, and Shrewsbury are squashed into those of their counties: Cheshire, Lancashire, Hampshire, Shropshire. Hampshire abbreviates as Hants and Northamptonshire as Northants; Oxfordshire and Shropshire use Oxon and Salop, which are abbreviations of their pseudo-Latin forms.

Sussex and Suffolk are divided into east and west halves; Lincolnshire is divided into the Parts of Holland, Kesteven, and Lindsey. Yorkshire, largest county of all, is divided into the East, West, and North Ridings (a dialect form of “thirdings”). Worcestershire has an outlying bit (Dudley) surrounded by Staffordshire. Areas settled by the Danes had another kind of unit called “Soke”: thus within Northamptonshire were the Soke of Rutland — which later became a full county — and the Soke of Peterborough — which was still in a sense part of Northamptonshire, until it was merged with Huntingdonshire; and its own northern part was called the Liberty of Peterborough.

And we haven't yet mentioned Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. The Welsh county of Flint is in two parts, separated by Denbigh. The most ornamental exception of all is in lowland Scotland: Kirkcudbright, with capital of the same name, is not a county but a Stewartry; and its name is pronounced sans most of the consonants: so it is not the county of Kirkcudbrightshire, but the Stewartry o' K'coobri.

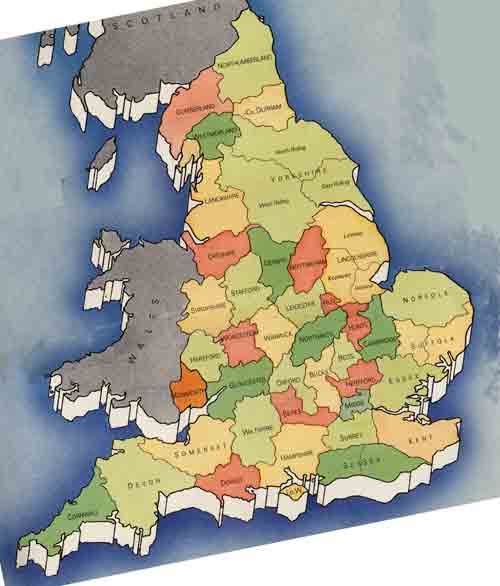

All this describes the traditional counties. There were forty in England and (if I've counted aright) twelve in Wales, twenty-nine in Scotland, six in northern Ireland, and one more: the Isle of Man. It was quite easy to learn them. As a child I was given a jigsaw puzzle map, with the pieces cut around the county lines (instead of in the meaningless meanders of the usual jigsaw puzzle), and after fitting them together twice I knew them by heart. (I'd like to make that puzzle again; the coloring wouldn't be needed for the counties, so it could be used to show the landforms.)

Middlesex was the first county (ancient kingdom) that ceased to exist, swallowed by Greater London in 1964. 1974 was when bureaucrats began seriously to meddle, in the high-handed and antipoetic manner that brings bureaucrats into contempt. The conurbation around Bristol was made into a new county of “Avon” by joining pieces from Somerset and Gloucestershire; similar conurbation-counties of “West Midlands,” “Merseyside,” “Greater Manchester,” “Humberside,” “Cleveland,” and “Tyne and Wear” were created by joining fragments from neighbors. The boundaries of three counties had radiated from the middle of the Lake District, because in earlier ages mountain regions were on the edges of society rather than sought out by tourists; but now, as if it was necessary to unite the Lake District like a conurbation, Latin-sounding Cumbria was created by abolishing Cumberland, Westmorland, and the piece of Lancashire that had been separated from the rest by water. Great old Yorkshire was dismembered into pieces that were not its old Ridings. Herefordshire and Worcestershire were united into — Hereford-and-Worcester. The interesting tangle involving Huntingdon and Rutland and the Soke of Peterborough and the Isle of Ely was simplified by smoothing all these into Cambridgeshire and Leicestershire. East and West Sussex became separate counties (but not East and West Suffolk); and West Sussex annexed Gatwick airport from Surrey. Berkshire lost its familiar boot-like shape by losing its northern bulge to Oxfordshire. Perhaps the most harmless change was that low-population Dorset gained, at its east end, the cities of Bournemouth and Christchurch from many-citied Hampshire. The most outrageous threat of all was at Dorset's other end: there was a proposal to give Lyme Regis to Devon! This at least was fended off.

Here's an example of the mess. Middlesbrough was in the North Riding of Yorkshire; in 1968 it became the centre of the County Borough of Teesside; in 1974 that was absorbed by the “non-metropolitan county” of Cleveland; in 1996 Cleveland was abolished, and Middlesbrough became a “unitary authority,” within the “ceremonial county” of North Yorkshire.

Wales and Scotland likewise were subjected to cutting-and-pasting. One can't object to most of the changes in Wales, where the new names were old Welsh ones: Gwent, Dyfed, Powys, and Gwynedd. Monmouth, Radnor, and Pembroke died as county names though living on as towns; the only names lost were Merioneth, Montgomery, and Brecknock (Brecon's county). But in lowland Scotland many small counties were swept away, including the three Lothians and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright.

Is all this logical? Logical, yes, though dividing the country into squares might be even more so. Does it matter whether counties (as opposed to electoral constituencies) are approximately equal in population? Not much, and they will keep becoming unequal again. So the bureaucrats have kept on tinkering.

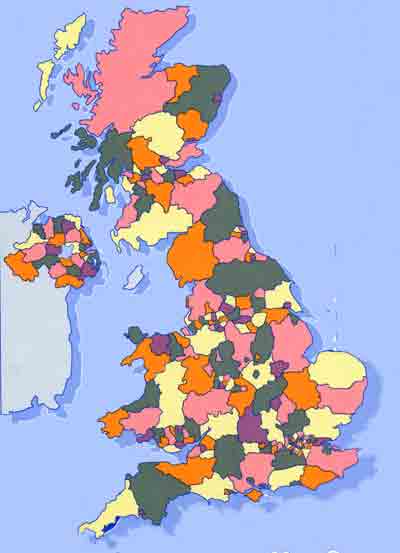

A 2002 map (and much will have changed yet again since then) showed an utter mess. There were Counties (which had County Councils above Borough and District Councils) and Unitary Authorities (which had only one tier of government). There were, as far as I can count (it's difficult), 104 Unitary Authorities in England, 24 in Wales, 20 in Scotland, 25 in Northern Ireland; most of them so small that on the national map 100 of them had to be marked with numbers, for which you had to search in nine lists around the sides. They included not only towns (such as Derby City) and parts of towns (such as Kensington & Chelsea) but areas such as West Berkshire (there was no other Berkshire), Telford & Wrekin, East Riding of Yorkshire (no other Ridings), The Vale of Glamorgan, and The Highlands (several former counties, larger than all of Wales). Some of the old counties, such as Denbighshire, had been revived, but were Unitary Authorities, not Counties. (Some of the Welsh ones had been changed back from Welsh to English — Dyfed and Gwent back to Pembrokeshire and Monmouthshire — others had not.) Such Counties as remained were, in a few relatively undisturbed regions (East Anglia and the southwest), the old counties, but most were the ragged fragments left after the Unitary Authorities had been torn out of their edges, or their middles. For instance Poole and Bournemouth had seceded from Dorset; Southampton and Portsmouth were holes in Hampshire. Somerset and Gloucestershire were separated by entities called North Somerset, Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol, and South Gloucestershire. Cheshire, Lancashire, and North Yorkshire were separated by a mass of about twenty patches of various sizes.

The result was a map impossible to learn. It was not quite as complicated as the maps of the Holy Roman Empire in historical atlases, but less interestingly complicated (the fascination of those Holy Roman maze-maps was the way the empires and kingdoms and bishoprics and palatinates overlapped each other).

I had found to my annoyance that the Ordnance Survey maps on the scale of 1:250,000, which cover the island in seven otherwise useful sheets, have ceased even to mark county boundaries. Now I see why: because they will probably keep frustrating mapmakers by changing.

Does it matter that the countryside in which Matthew Arnold's Scholar Gypsy wandered, and over which Thomas Hardy's Jude gazed toward the distant towers of Christminster, is now not in Berkshire but in Oxfordshire? and that masses of other books, articles, and historical materials refer to villages in Berkshire that are now in Oxfordshire or in “Reading,” “Wokingham,” “Bracknell Forest,” or “Windsor & Maidenhead”? I think it matters. Does it matter that children and voters can't possibly learn the map of their own country (whereas it is no more out of their power to learn the states of the U.S. or the countries of Africa or even the departments of France)? — does it matter that they can't be expected to know what state the terminology has reached, and therefore how to refer to the areas where they or their cousins live? I would think it has practical consequences for their citizenship.

People have to ignore, in daily life, the “Unitary Authorities” and other fiddlings. They still say they live in Middlesex (the longest-lost of counties) and use it in personal and business addresses. A handbook of town maps has to be about “Hampshire” and include the pieces such as Southampton that have been torn out of it. A newspaper article refers to Dyfed — as it was before the last change and after the change before last.

It would be perfectly possible for the county boundaries to remain where they historically were, while officialdom organizes and reorganizes councils in whatever units it likes. If for practical reasons there has to be a Bournemouth Council as well as a (rest of) Dorset Council, they could both be in Dorset without one being set over the other.

There is a story that the bureaucrats wanted to replace the county names with numbers, so that Dorset would have been Sector 29. This — I hope — is apocryphal. But the numberheads are pushing us toward, and will be happier when we are all pinned down in, a world where we need nothing but our postal codes.

I believe there is a society for restoring the Forty Traditional Counties of England (though its address isn't shown on the map someone gave me). The people of the little town of Appleby, formerly the county town of Westmorland, voted to change its name to Appleby-in-Westmorland, to protest the sacrilege and to keep the abolished name in existence.

|