We learned from a recent newspaper item that there is a list of Britain’s “Top Ten Beaches,” calculated annually from “TripAdvisor reviews and ratings.”

1 Woolacombe in Devon

2 Weymouth in Dorset

3 St. Brelade’s Bay on the island of Jersey

4 Rhossili Bay near Swansea in Wales

5 Porthmeor beach at St Ives in Cornwall

6 Fistral beach at Newquay in Cornwall

7 Porthminster beach at St. Ives

8 Perranporth in Cornwall

9 Hengistbury Head near Bournemouth in Dorset

10 Luskentyre on the Isle of Harris in Scotland

On what criteria? For Woolacombe, reviewers mentioned surfing, and the beach huts for hire. Weymouth’s beach is a large stretch of sand in front of a town. Not mentioned was the most beautiful place in the world.

Yes, superlatives can be as objectionable as Lists. Still, that’s how I described it when persuading others to revisit it with me.

I discovered it when revisiting Britain one March and cycling along the coast. The cliffs of Cornwall have indentations called coves – Sennen, Porthgwarra, Lamorna, Mullion, Porth Curno. Many of them are around the “toe” of Cornwall, near Land’s End and the resort towns of Penzance and St. Ives, but this one, Kynance Cove, is on Cornwall’s “heel,” the peninsula called the Lizard. March was cold, so when I found my way down a devious path into this wonderland I had it to myself.

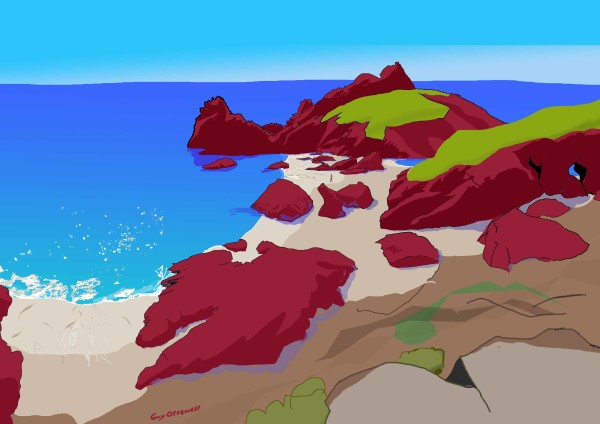

The rocks don’t really show this overall color. They are, from a distance, black-brown. But as you go among them and slope around some corners, you find beside you, sometimes in overhangs, glossy surfaces of a red so deep that it verges on black, the color of an Arkansas Black apple. So in my mind Kynance is made of this rock. It is a metal-rich mineral called serpentine, formed at hot pressure deep in the Earth’s crust and writhing up in steep strata. The gaps eroded in it were of a softer rock: granite.

The best time is when the tide is receding. I stood for an hour gazing at the systems of channels carved into the sand, as subtly braided as in an Arizona wash or Arabian wadi after a rain. Then I watched for another hour as the tide came in and cut me off in one of the sandy inlets among the rocks. The sharp contrast between the hard serpentine rock and the soft malleable sand is the beauty of Kynance,

Then I discovered that over a saddle of sand – covered at high tide – is a beach on the other side. And from that, you can venture into clefts, one of which is a cave through which you can venture back to the beginning. (I’ve also distorted the picture somewhat by moving and opening a hill to give a glimpse of the farther beach and the tunnel.)

Kynance doesn’t need to be on the Ten Best list. In summer, and perhaps even March in this age of tourism, you’d have to share it with a hundred people. Still, as every tide comes in it erases their footprints and begins again the miniature rivers.

Hmm. We have a lot of serpentine rock along the California coast. Serpentinite minerals form when the Earth’s mantle is exposed to water along a tectonic plate boundary, and we see them when later geologic activity either lifts them to the surface or wears away overlying layers. So far as I know, all of our California serpentine rocks are green. I didn’t know that serpentine could be other colors. But apparently “serpentinite” is more of a general recipe than one specific molecule, and it will have different colors depending on the different elements in the stew.