|

Halley's Comet from the Inca Way

I was in Cuzco when an earthquake struck; afterwards a crowd of

three or four thousand came to the main plaza for a visit by president

Alán García (he passed a couple of yards from me, munching a choclo

or corn cob that had been presented to him); then in the evening

a crowd I estimated at eighty thousand gathered to mourn those killed.

Here is part of my account for myself, just about the walk to Machu

Picchu:

I had once seen a newspaper article about the "Inca road," a spur

of which ran to Machu Picchu; and part of my idea in coming to Peru

was to walk some of it. To paint it would fit my theme of painting

roads. I imagined it as a rock-cut gallery slung between the peaks

of the Andes. Actually it was a multiple system thousands of miles

long, the Qhapaq Ñan, "mighty way," webbing the empire from Ecuador

to Chile; much of it in steps, since the Incas had no wheels. Its

starting-points were four roads leaving Cuzco (Qosqo, the

world's "navel") for the Tawantin-suyu, the "four quarters" of the

world or rather of the elongated Inca empire: Chinchaysuyu stretching

northwest to Quito, Cuntisuyu down to the coast on the southwest,

Collasuyu southeast to the lake and beyond, and finally Antisuyu,

the descents to the unconquerable jungles on the north and east

— the anti, the original "Andes." (Is there a singular

— El Ande?)

Certain streets off the corners of Cuzco

plazas marked the beginnings of these roads — the roots, the

germs, of the four quarters of the world. But I had not walked far

from the Triunfo up Hatunrumiyoc, the root of the Antisuyu road,

before becoming lost in backyards and hillsides. But a fragment

farther out leading to Machu Picchu had become a recognized objective

for hardier tourists, known as "the Inca trail," camino

incaico; walking it required three or four or five days; there

were guidebook descriptions of it; "don't start it unless you can

go all the way — once you're in, the only other way out is by

helicopter." (But how d'you let the helicopter know you need it?)

The men of the Australian party we had met on the train planned

to walk it, leaving on Monday, so I asked to join them. I didn't

know whether I could until a meeting they held on the Saturday night.

Eleven were going; Carlos, their local factotum, took lists of tents

and cookers and backpacks to be rented. But by then all the ordinary

shops had shut for fright of the earthquake, so I could not buy

food; I decided to wait two days till I could be better prepared,

except that I would have to go by myself. And it was raining, and

there was the last aftershock of the earthquake; only four of the

eleven went. I bought food (packages of soup) from those who weren't

going; rented tent and cooker; but I still had little food, and

no sunburn-cream, insect-repellent, or (potentially worst of all)

iodine for purifying water. I had no boots, and, my feet being unhardened,

might not be able to make it with bare feet. I went looking for

shoes to buy, and the best shoes I could find were white plastic

city-slickers closed with velcro straps — more suitable for

a dance-hall!

There was now a railway carved down along

the Urubamba gorge to Machu Picchu and beyond, and that was the

way the thousands of tourists went. The tourist train went non-stop,

in four hours; but the local or "Indian" train stopped everywhere,

so you had to be at the station very early in the morning to get

a place on it, and get off it at "Kilometer 88."

The railway mounted the slope closing the

valley immediately west of Cuzco by reversing direction five times,

like a road with hairpin bends. It ran through the upland valley

of Anta; descended to the Urubamba by a tributary river, losing

height at one place with another pair of reverses.

I got off at Kilometer 88 with two French

people, two Japanese, and four Israelis, but left them behind and

never saw them again. I crossed the river; the path at first doubled

back up the left bank, then up the long side-valley of the Cusichaca,

which descended from Mount Salcantay. Most of the first morning's

walking was swift and pleasant: light woodland, a "pass" which was

no more than an easy rocky wrinkle in the valley floor, cultivated

terraces (partly natural, since the river had clearly cut down through

an earlier valley-level), small ancient settlements which were still

settlements (Llaqtapata, Wayllabamba). I had a crude but useful

picture-map that I had found in a Cuzco shop, and on its margins

I noted about fifty of the first plants and animals I saw (a few

of them domestic). Humming-birds, caterpillars, thirty-foot century-plants . . .

Up a side-valley from the side-valley, the Llulluchayoc. In only

three hours I had reached a glade beside another side-stream where

a large party of Canadians was just finishing lunch, cooked by Indian

bearers. After they left I heated the soup I had, and it was so

salty that I had no more of it but was thirsty for the rest of the

journey. As the trail steepened and roughened I had to put on the

absurd white shoes.

In Cuzco, or anywhere else I had been, I

knew I was living on thin oxygen when I went up stairs and got breathless;

otherwise the only evidence of the altitude was the cool weather.

Now the rocky ascents of the trail became progressively less blithe

to climb with sixty pounds on my back. The upper valleys ascended

so steeply that to turn around was to look out between wings of

mountainside into a white void, below which was the world I had

come from. Some long forking landslide-scars on mountainsides far

above the earlier valley were now below eye-level.

At one thickly wooded place where the trail

disappeared into a stream, I turned left up what I thought was the

continuation though almost vertical; I thought it would climb a

bank and then turn along a level ledge; it became only worse and

obviously wrong, but it would have been so hard to back down that

I kept on forcing upward through denser growth looking for a sidewise

ledge, and lost an hour on this hillside. At four o'clock I came

to the beautiful meadows of Llulluchapampa, grassy steps interlaced

by streams, rocks, and waterfalls, at the foot of the "First Pass";

others were pitching camp, and I did too, in a shower, with a rock

at my back, on my own little ridge of grass, between brooks which

each emerged from underground and then fell through a clifftop.

In the miserable damp little tent I did

not sleep much, and took to cantilevering myself out backward through

the door to try to tell the hours till dawn. It took me the longest

time to get my bearings, because the tent was blocking the north

and the sky was upside down behind and over me. But there in the

pure and now rain-free air was the Milky Way, and the Coalsack Nebula,

and Halley's Comet. It was just now, in the night between April

9 and 10, nearest to the earth. It was about as large to the naked

eye as it had appeared in binoculars in the north; a little triangle,

because the tail widened rapidly but faded out rapidly.

In the morning I started ahead of the other

campers up the last and steepening way to the "First Pass," Warmiwañusq'a,

the highest (13,680 feet, not as high as the railway pass south

of Cuzco). I stopped often to sob for breath; and after an hour

Indian bearers began to overtake me. They looked strained, of course,

but nothing like as strained as I was; and they went, in their rough

sandals, at almost a trot. I tried it but could not keep it up.

Some of them were carrying tables! I passed them taking a rest,

in one line along the path-side: there were no fewer than twenty-six.

They were paid sixty intis a day — three or four dollars —

I wouldn't have done it for sixty dollars an hour! The pass-top

at last came close, through a maze of rockwork. A lone century-plant

grew on the skyline. When I was on top, one more tall burdened Indian

came striding up and over and started straight down the other side

without a pause.

A couple of thousand feet down I met a fellow

coming back up: he had dropped his camera somewhere. He later told

me that one of the people in the party now coming to the top of

the pass felt so miserable from altitude-sickness, which people

often got above thirteen thousand feet, that she handed him her

camera, and he took 225 photographs with it on the trail. (Thirteen

thousand feet, by the way, is the average depth of the abyssal plain

of the oceans.) I was drawing fewer and fewer sketches — I had

to heave the whole pack off my back to get at my sketchbook —

and they were so sketchy as to be intelligible only to me. How could

I, with a scratchy point on a little page, indicate these enormous

interlocking sails of slope, and the immense raise of the eyes to

the pass where I had earlier been? In this second valley-system,

the Pacai Mayu, I became worried that I was on a side-trail leading

out of it too high to the south, because I seemed to be clambering

across a slope rather than following a valley; not till coming correctly

to the ruins of Runkuraqay did I realize that the valleys shown

on the map were more like drainpipes down the side of a house. By

these ruins (a very short day's stage) the twenty-six Indians were

setting up the next camp for their clients — tents and even

latrines. The first visible bit of road-masonry started just before

Runkuraqay. This whole "Inca trail" really was a piece of the road-system;

it was the only way from the upper Urubamba (hence from Cuzco) to

the lower Urubamba (Machu Picchu and other hidden cities). For down

to the right was the Grand Canyon of the Urubamba (the gorge starting

at Torontoi), virtually impassable till the railway was blasted

along it; up to the left was the range of Salcantay and Soray, too

high to cross (or almost — there was a severe pass between those

two peaks). This was why the road struggled up and down over such

notches as it could find in the ridges descending from Salcantay.

For the rest of the long day I walked without

seeing anybody, over the second pass with its wild boggy lakes above

the upstreaming clouds, past caves and the ruins of Sayaqmarca,

bathing in a jungly waterfall. The trail became almost continuously

paved, the best part being a causeway snaking across a marsh that

filled a large pocket in the mountainsides. It was hardly easier

to walk on than the black mud or sandy groove or virtual streambed

found elsewhere: the blocks were rough, the bigger ones set at the

edge, the rest a stony prickle along which I had to pick my way

with eyes down. (A microcosm of the Andes themselves: flat-topped

causeway exceptioned by peaks and gashes increasingly toward the

edges.) The trail was essentially level as it skirted high along

the rim of the Aobamba valley; but I was tiring more, not less,

on such climbs and descents as there were, probably because of having

too little to eat. In places this five-hundred-year-old road had

fallen away or been buried by avalanches. In two places, slabs of

rock larger than churches had slid down and settled over it; I had

to get past behind them by "tunnels," long enough that I was stepping

by faith in complete darkness. My pack projected above my head,

and often the vegetation when I ducked under it caught me (bringing

down showers); for it was now dense enough to be called jungle,

with bamboos and lianas mixed in. You could rather easily slip on

a wet block or be catapulted off the trail by a branch; it must

happen a few times a year; usually there is a drop of five hundred

or fifteen hundred feet beside you; you most likely would get stopped

by vegetation not very far down, but it would be tough to struggle

back up, especially if you had been knocked on the head; you'd just

become a statistic; in short I could see why it wasn't entirely

a good idea to be alone. For some hours of the afternoon I was walking

inside cloud, which thickened to heavy rain, then ceased early enough

for me to walk myself dry. Then I came to the most thunderously

abrupt view:

The narrow masonry trail, following a contour

along the dark left-sloping hillside, approached a saddle. The trail

curved leftward to get onto and run along this saddle, which was

only about twenty yards long; from its farther end the trail curved

left again and thus ran away along the same contour on the same

back-side of the ridge, without having crossed it. But from the

paved saddle, as from a balcony, I looked down over a mighty void,

at the bottom of which was the Urubamba! Two fragments of the gleaming

band of water could be seen, twisting to hide themselves among the

boots of the ridges. The saddle must have been at about twelve thousand

feet, the river at about six thousand, and the angle approaching

forty-five degrees, which when you are looking down seems near vertical.

The trail kept westward at about the same

level to Phuyupatamarka, where I certainly had to camp, having walked

several times farther in the day than would be sensible if one were

properly supplied and wanted to enjoy it. Two and a quarter days

all together; people usually take three to five; on level ground

33 kilometers would be only a day.

I had even rebelled against the idea of

a tent. Now it was raining solidly as I pushed the skewers into

a soggy marsh of straw, spread on a spur below the top of the hill

which was already occupied by campers with, again, Indian cook-bearers.

This was the longest night; I didn't sleep at all; but what can

you do for thirteen hours of darkness on a pinnacle between canyons?

Again the rain gave way to crystalline black air so that I could

watch the comet tracing the slow hours above me.

I got up as soon as I could, and it was

none too soon to see the most overpowering dawn. The screens of

mountains descended zigzag-topped to the right, mostly below me,

cloud-layers floating in the chasms between them like water in docks;

all was in violet darkness, except that the high leftward crest

of the farthest range, about six sharp icy peaks, nevadas,

caught and threw back the pink blaze of the lowest light. And just

above hung at an angle an orange fish of cloud. Straight below me

was a sort of terraced stone ship with curious apertures: Phuyupatamarca,

the largest and most complex ruin so far.

An Indian was playing a flute in the otherwise

dormant camp behind me. The path went down past Phuyupatamarca and

was from then on almost all the way (instead of just in many parts)

a staircase of deep rough steps. In fact it descended four thousand

feet without pause. This unrelenting crashing down from block to

block did in my legs. The jungle that filled the damp slot was ever

more multifarious in its plants and insects and birds; there were

butterflies with electric blue underwings. When I first came in

sight of the mountain of Machu Picchu and its smaller but sharper

prow, Huayna Picchu, both looming above the tourists who arrived

up to them, they were far below, small as toothpicks. They

barely pricked into the sunlight that grazed down into the cavernous

valley. This was the more-vertical-than-horizontal environment of

my imaginings. I passed a small camp of people who, in exchange

for correct information about how to see the comet (they had been

looking at Jupiter), gave me maté de coca to drink and some

coca leaves to chew. A bare slope leftward from this ravine to Wiñaywaina

(also spelt Winayhuayna and said to mean "eternally young"; I read

that a satellite city was discovered there seven years later). The

last roughly level miles were along some of the sheerest cliffsides,

with bridges of sticks across gaps in the ledge, and the Urubamba

two thousand feet below. Finally Intipunku, a sort of gatehouse

fortress, on the corner of the shoulder of Machu Picchu mountain,

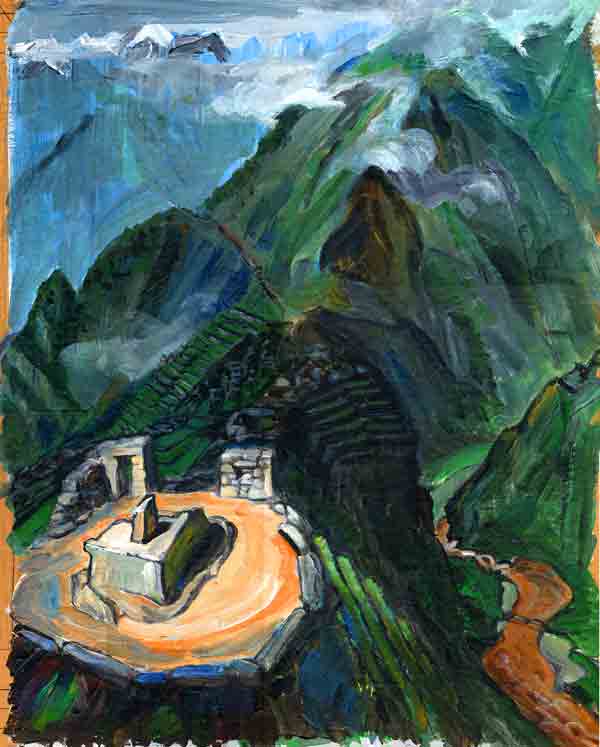

and the view down over the green-and-grey tracery of the city.

BACK

|