|

Dyehouse North of Greenville toward the Blue Ridge is Traveler's Rest, and

a mile north of that is the Renfrew mill village where we were living.

Only some of the houses still housed mill workers; formerly the

company had owned them all, houses and people, marrying them, selling

them supplies in the company store, giving them one week off (the

week of July 4), and expecting to see them on the baseball field

and in the church. “Mill” in South Carolina meant a cotton

factory. Textile was still the regional industry, though the boll

weevil had wiped out the actual growing of cotton forty years ago.

The company was Abney Mills, the most archaic. Its other mills around

the upper state were for weaving the cloth; this one, Renfrew Bleachery,

was for the bleaching, dyeing, and finishing. The mill and especially

its chimney overlooked us, belching smoke, and bellowing a siren

three times a day for the start of shifts. I wondered what life

was like inside, and went to work there. I was a few weeks on the

afternoon shift, then the shift that started around midnight and

ended around dawn. The minimum wage was a dollar ninety-nine an

hour. I was in the smallest of the three departments, the dyehouse,

very much a junior under kindly old foreman Doug and terse mighty-armed

Allyn. We stood around until a work order was brought to us, and

then Allyn said “Get yer gleuves,” and we drew on our

rubber gloves and fetched hefty barrels of chemicals and tipped

them into the vats for mixing to the quantities of dye that were

to be piped to the machinery. There were no safety regulations.

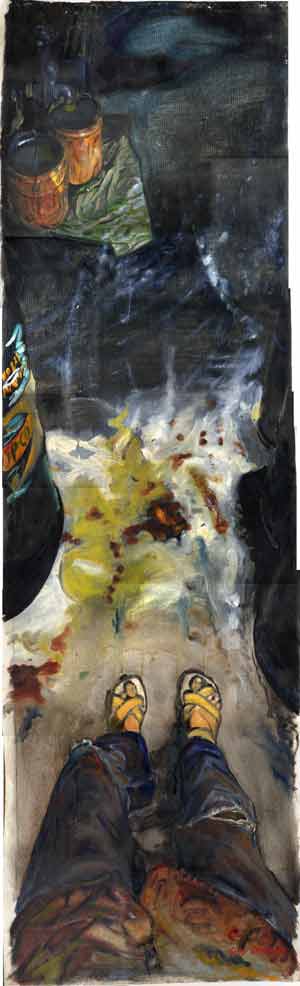

Lethal chamicals sloshed everywhere. I built (at home) an oil painting

of the luridly colorful floor, with my feet on it in sandals. |

After a while they did make me wear rubber boots. The scenes among

the machinery, the rivers of cloth flowing over rollers and through

tanks and being snatched away in clouds overhead — I made pencil

sketches on the backs of work-order sheets. Eventually I couldn't

conceal all of these; and the men got me to draw portraits of themselves

to take home to their wives. There was so much to observe that I

had to build a string of mnemonics in my head till it was almost

too long to remember, then dodge to some spot where I could jot

it, also on a worksheet, and scrunch it into my pocket, and start

again. Inevitably this too became known or sensed, and I found myself

politely summoned into one of the distant offices where the managerial

classes worked. Was I an industrial spy? On Abney Mills?

After a while they did make me wear rubber boots. The scenes among

the machinery, the rivers of cloth flowing over rollers and through

tanks and being snatched away in clouds overhead — I made pencil

sketches on the backs of work-order sheets. Eventually I couldn't

conceal all of these; and the men got me to draw portraits of themselves

to take home to their wives. There was so much to observe that I

had to build a string of mnemonics in my head till it was almost

too long to remember, then dodge to some spot where I could jot

it, also on a worksheet, and scrunch it into my pocket, and start

again. Inevitably this too became known or sensed, and I found myself

politely summoned into one of the distant offices where the managerial

classes worked. Was I an industrial spy? On Abney Mills?